Any Idea What We Have in Mind?

Take, for Example, Democracy

The essence of this paper is to draw attention to an obvious distinction of which we are well aware — and consequences about which we typically have our eyes closed.

For an example of the distinction, contrast two different pieces of reasoning:

(a) “If Benjamin Netanyahu continues as Israel’s prime minister, Israel will take over Gaza and the West Bank; Benjamin Netanyahu will continue as Israel’s prime minister; therefore Israel will take over Gaza and the West Bank” with

(b) “the democratic vote in Israel led to Benjamin Netanyahu’s government being formed, therefore the resultant Israeli policies are justified”.

Another example is the contrast between the following two claims: on the one hand

(c) “There is no largest prime number” and on the other hand

(d) “All human beings should be treated fairly”.

Reasoning leads most people by far to grasp the validity of (a), of how its conclusion does logically follow from its premisses, and the truth of (c) once the terms are fully explained, but (b) and (d) generate heated arguments — well, they do once what is meant by a ‘democratic vote’ and ‘fair treatment’ is specified. The topics of liberty, free speech and justice similarly generate heated arguments.

Politicians, commentators and newspaper-letter writers have spoken and written millions of words on (b) and (d) and related ideas, but disputes continue. The response could be that those individuals typically lack the knowledge, erudition and rationality of philosophers, political theorists and similar others — even sociologists — who have spoken or written in great detail on such subjects. That response is true, yet it is irrelevant for although millions of words have indeed also been written and spoken by the knowledgeable, erudite, scholarly and rational, disagreements continue with regard to what constitutes democracy and fairness and why they should be valued (if they should).

The same holds regarding the concepts and applications of liberty, free speech, rights, justice and dignity. Millions of words — numerous books and articles — have been written on those topics, be they by the erudite and thoughtful or by newspaper columnists and politicians, yet radical disagreements persist.

To keep this paper accessible for a quick read, allow me to focus on democracy; it also involves the nature of fairness.

Democratic countries congratulate themselves on being democratic and are ever ready to spot, mock and condemn sham democracies. Witness the repeated self-praise by Israel as the sole genuine democracy in the Middle East. Witness how the UK proudly declares that it is a long-standing parliamentary democracy. Witness too President Trump in maintaining that in the 2024 US election he won the democratic popular vote. Now, we may quickly agree that a democracy is a sham if there are no ‘free and fair elections’ and if those opposed to a current government are prevented from standing for election be that prevention by means of murder, convenient accident or legislative constraints, but that does not address the question of what is it about a democracy that does and should generate so much praise. To answer that question, we need to have some idea of what a democracy is.

Democracies are sometimes declared valuable on the basis that democratic countries are more likely to lead to valuable outcomes for citizens than are non-democracies. What counts as valuable outcomes and what justifies that likelihood claim pose a new set of questions and worries. My focus, though, is on the democratic procedures and how, disregarding outcomes, they are or should be valued. After all, we need to know what constitutes a ‘proper’ democracy if the claim is that such democracies have good outcomes for countries and indeed for international relations between them.

The basic best that can be said for a democracy in itself is that citizens are able to engage with a state mechanism that leads to government and governmental policies. That is, there are procedures whereby citizens can all participate equally in determining the laws that govern them. A little thought shows that that is, though, an extremely minimal condition and with the unclarity of ‘participate equally’. Further thought should bring to light that even that minimal condition fails to hold in self-congratulatory democracies such as US, UK and Israel.

Consider first the conditions that are set — democratic hoops through which we must leap — for having a vote and managing to cast the vote. The conditions impose heavier burdens on some than on others, for example, via the identity documentation required. Is that treating would-be voters fairly, allowing them to ‘participate equally’? Further, before you even get to casting votes, consider the conditions that are imposed to determine which individuals may stand for election; consider also how the representatives of political parties are chosen. Those factors lead to restrictions on voters' choice — both with regard to candidates and, indeed, the policies on offer. Reflect too on how, because of large discrepancies in wealth and influence, there is considerable unfairness in the amount of funding and exposure available to candidates and parties.

Of course, there are further features of our democratic elections that may undermine their value for participants — namely, restrictions on what may or may not be said; the information and misinformation available to would-be voters; the presentation of policies on offer; and the ability of the voters to evaluate what is said. That leads into muddy and muddling questions of when advertising political views becomes indoctrination and when beliefs can be rightly treated as authentic. For example, many condemn elected governments as ‘nannying’ when seeking to coax consumers into healthier eating, yet are silent when political parties seek to coax voters into voting for them or — for that matter — when unelected powerful corporations tempt consumers into excessive gambling or undesirable purchases.

Consider secondly how the results of votes cast in an election determine the eventual democratic government and which individual is brought into power as a prime minister or president. First, there are the distortions, some deliberate to aid one party rather than another, by the boundaries drawn of constituencies. Secondly, there are the differences manifested between direct elections and voting for representatives. Some procedures are based on ‘first past the post’, some by one or other version of proportional voting or having an ‘alternative vote’ system. Thirdly, once we have the elected representatives, witness the wheeling and dealing that frequently takes place to secure a government; that wheeling and dealing can generate hugely disproportionate power to minority groups. A clear recent example is the highly disproportionate influence of the right-wing religious Zionist ministers in the Netanyahu government.

Considering the above, we see differences and defects in our self-congratulatory democracies. Is there a basic feature that makes them all worthwhile qua democracies — or that rightly leads to praise for some and not for others?

As ever, we need to recognize that we have here matters of degree, the degree to which the diverse, different and conflicting beliefs, wants and aims of citizens are in some way handled to ensure that a state can be governed. Inevitably the resultant government is unlikely to be approved by a majority of citizens.

Allow me to add a nuance to my observation that citizens hold diverse and conflicting beliefs, wants and aims. Most, maybe all, citizens would agree, as indicated above, that elections must be ‘free and fair’, but that does not show that they agree over what constitutes ‘free and fair’ — far from it. Some democratically inspired argue that there should be no limits on financial spend and publicity deployed by candidates and parties; others argue that there should be severe limits or even that the main funding of parties should be by the state.

A third consideration is highly important for all democracies. Whatever the democracy, however much praise it receives, however much it may claim to have ‘free and fair’ elections, the democratically generated laws may yet offend other values of the typical democracy-lover — the value, for example, of equal rights or free speech. A free and fair election or a free and fair referendum may lead to a law that many would deem repulsive — such as the institution of slavery of a minority or pushing desperate migrants arriving on small boats back into the sea to drown.

The above third consideration reminds us that not all matters of how a state should be run, its laws and international polices, can be settled by democratic procedures. A prominent current example is the misleading rhetoric of the Israeli government that seeks to justify as acceptable its horrendous attacks on Gaza’s civilians and on the Palestinians in the West Bank by declaring how those attacks result from policies of a democratically elected government.

Overall, what may be said in favour of certain democracies is how populations in the main acquiesce in what they have got and do not try to overthrow their democracies. The democratically disgruntled usually seek to introduce different democratic procedures by using the democratic procedures currently in place. Of course, that is not always so.

Securing the ‘votes for women’ in the UK, around a hundred years ago, involved protests, some disruption, some violence, though those in power today conveniently overlook that fact. Those in power today are ever ready to condemn extra-parliamentary protests if they involve virtually any disruption.

I controversially point out: were activities to be occuring today in the UK, similar to those by the ‘votes for women’ movements decades ago, they could well be banned as ‘terrorist’. Witness how currently in the UK, peacefully sitting down, holding a placard with the inscription “I oppose genocide in Gaza”, with or without the added “I support Palestine Action”, is deemed terrorist. Is that how a democratic government should operate? That question certainly manifests another example of disagreement — in this case, over the application of fairness in determining which speech should be freely permitted.

◊ ◊ ◊

The beginning of this paper referred to how we have eyes closed to the consequences of a distinction, a distinction between matters manifestly not in dispute and matters, once with a little digging, clearly are in dispute. My ‘manifestly not in dispute’ were examples from logic and mathematics, but I could have used certain examples from the sciences, technology and engineering — whereby we know how to generate electricity, how to vaccinate against measles and, indeed, how to maximize casualties in warfare.

My ‘manifestly in dispute’ related to the understanding and application of certain values that many people hold or, at least, which receive lip-service support. Despite the time spent by thousands over the decades, indeed centuries, writing about, teaching, lecturing on these values and noticing ever finer distinctions, there is no body of knowledge about the right way, for example, to run a democracy. By the very nature of such values, I suggest, there cannot be that knowledge.

The above observation is not to dismiss the labours by academics, the scholarly and the erudite, in those fields as lacking value. Activities — such as reasoning, analysing, reflecting, discussing — can be valuable in themselves without there being a distinct valuable outcome.

That observation may well apply to this paper.

By way of coda, it does not follow from the observations in this paper that there are no facts of the matter regarding any valuations whatsoever. You ought not, for example, to torture this child in front of you — or, indeed, this cat or dog or giraffe — solely for the sheer fun you may get out of doing so. That is a fact that many people can grasp and there must be something about the world and about people to make that valuation claim true — after all, what else is there?

◊ ◊ ◊

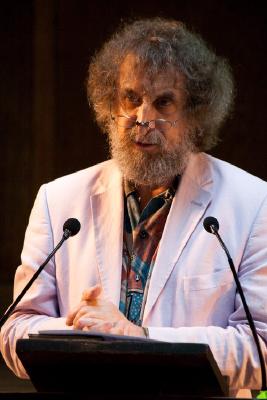

Peter Cave is a popular philosophy writer and speaker. He read philosophy at University College London and King’s College Cambridge. Peter is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, Honorary Member of Population Matters, former member of the Council of the Royal Institute of Philosophy and Chair of Humanist Philosophers - and is a Patron of Humanists UK. He has scripted and presented BBC radio philosophy programmes and often takes part in public debates on religion, ethics and socio-political matters. His philosophy books include This Sentence Is False: An Introduction to Philosophical Paradoxes (2009), and three Beginner’s Guides: to Humanism, Philosophy and Ethics. More recent works are The Big Think Book: Discover Philosophy Through 99 Perplexing Problems (2015), The Myths We Live By: A Contrarian’s Guide to Democracy, Free Speech and Other Liberal Fictions (2019), and How to Think Like a Philosopher (2023).

Find out more about Peter Cave at: www.philosophycave.com.

Peter Cave on Daily Philosophy: