Interview with Paul B. Preciado

Philosopher interviews

The interview took place in Rome at the Cinema Festival. I had met Paul B. Preciado near the Auditorium, and by all accounts, I should have addressed him as a director. This is where my first mistake lies. Paul was there to present, with his Italian publisher Fandango, his first film—a hybrid of autobiography and a celebration of the first truly queer thinker in Western history, Virginia Woolf. The film is titled Orlando: My Political Biography, and it contains much of Preciado the philosopher and writer. Preciado, who was once named Beatriz, often shares the fate of philosophers who begin to experiment with other genres: limited acceptance in philosophy departments, yet an aura in critical studies, fashion, design, contemporary art, and cinema comparable only to that of Pier Paolo Pasolini (who, similarly, was reviled by the literary intellectuals of his time). He has revolutionized gender studies, eloquently documented his own transition (from woman to man), explored the philosophy of pornography, and reinterpreted philosophy through the lens of non-patriarchal, cognitive pleasure. A few years ago, Gucci, under Alessandro Michele, inadvertently turned him into a star: he was the protagonist of a landmark video that cemented him as “Preciado,” one of the most influential intellectuals of our time. But why a film? And why is queerness fundamentally linked to a research methodology and only subsequently to the recognition of a “liquid” metaphysics for constructing the identity of things, persons, and events?

Leonardo Caffo: Paul, this is your first film. This is the fourth or fifth interview I’ve conducted with you, but a directorial debut was not anticipated. Or at least you never mentioned it. What can you express with a film that a book cannot convey? Is this choice to mix genres, to create video, also a queer act?

Paul B. Preciado: Well, I would say that I am primarily interested in the idea itself. The idea in itself. Then, in a second phase, I tend to find the best medium without any preconceptions. For me, it is always a way of doing philosophy, and perhaps we should ask ourselves what “doing philosophy” means today… things have changed. I no longer believe that an article or a book is inherently more philosophical; contemporary life demands that we know how to use different media and understand which medium is the best possible instrument for the theories we wish to defend. I was given the opportunity to make a film, and I was given the freedom to do it: I consider that fortunate. I chose to stop teaching at a university and resigned from my professorship in France. I do not believe the academic structure is any longer minimally entitled to distribute the necessary impetus for knowledge to truly act in the world… we must experiment in every field.

Leonardo Caffo: Are there connections to your previous work as an actor for Alessandro Michele and Gucci?

Paul B. Preciado: No, I wouldn’t say so. Of course, it was still an experiment with moving images. I am friends with Michele, and it was also nice because another dear actress friend, Silvia Calderoni, was with me, but I do not esteem the fashion industry, not at all: it is energy-intensive, violent, and terrible. It’s simply not my world. This does not mean that Prada or Gucci do not create interesting things with the right creative directions, but I do not want my name associated with the world of fashion… I am only interested in how one can transform or play with a body, working beyond its identified paths and identity barriers. Not fashion as such. And I do not, under any circumstances, want people to think I was advertising someone or something.

Leonardo Caffo: Yet, as you speak, I think… the film industry is not exactly healthy or sacred either…

Paul B. Preciado: You are right. The cinema industry, strictly speaking, is also violent: in fact, I do not want to be called a director, much less seen as a worker in that industry. I merely made an attempt. Orlando is a film where I try to invert many things, including the role of the actor. I politely ask the participants if they want to share their stories, which I always approach on the metaphorical ridge… I do not impose a script; I listen to them from Orlando to Orlando. And, to connect the things you asked me… had I not worked for Gucci, this film would not exist because I used much of that money to produce it out of my own pocket. But I am proud of it.

Leonardo Caffo: So how do you inhabit this evident contradiction?

Paul B. Preciado: Every medium can be used well or poorly. One must not blindly incorporate the norms of the medium they are using but attempt to deconstruct it from within. Judith Butler, for example, taught me this very well… the battle from within, against the coercive surveillance present even in seemingly creative and neutral tools. I always do this, even when I write a book… it is not so different with cinema. And this is also the meaning of many scenes where I show the “behind the scenes”… I try to dismantle cinema from the inside.

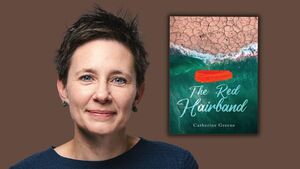

Image supplied by Paul B. Preciado.

Leonardo Caffo: You are one of these Orlandos, starting with your name: “Paul” which derives from one of Michel Foucault’s given names that he used when visiting gay clubs in prohibitionist Paris…

Paul B. Preciado: Only you could ask me this question! Yes, that is correct: I deeply value this aspect of “epistemologies of proper names.” Paul is my name precisely because it is not my name: an anti-category where one can find refuge from the paths of the binary, patriarchal world, so focused on stringent ontologies and taxonomies. This is the violence of metaphysics. Orlando is the attempt to stop categorizing the forms of the spirit… trans, queer, non-binary… and simply say, “I met another Orlando.” I would say that, yes, this is a truly significant political conquest. Because if my work does not have a political implication, then it was not good work. In fact, we used the festival’s red carpet not just for me or the actors, but for a small militant queer walk… these are small signals.

Leonardo Caffo: The Queer question, therefore, is against the possibility of a strict identity and not the creation of new identities. This is something that should be explained to newspaper feminism… without controversy, but truly to move beyond.

Paul B. Preciado: Exactly. Of course, for every minority, it is primarily important to affirm its identity, especially if it has been repressed or erased for millennia. In the second place, however, and this I believe is the true objective, one must move beyond the boundaries of new identities and question the very concept that an identity truly exists. This was already present in Woolf’s book (which begins with the historic phrase, “He, being no longer of a fixed sex”), and this is why both she and I play with the idea of “biography”… constructing the narration of an I starting from a we. To fluidify the forms of subjectivity, to get lost without ever finding oneself again: because it is not necessary, and it is profoundly liberating to inhabit a liquid world that is not rigidly stable. This is my anti-ontology, my response to much of the philosophically patriarchal system that trained me when I studied in Paris with Jacques Derrida or in New York and Princeton. We can rewrite the theory of knowledge, but with what goal? To liberate the Orlando that each of us truly is.

Leonardo Caffo: As we speak, Paul, Palestine has been invaded in response to the terrible Hamas attack against Israel. How can we concern ourselves with gender rights at a time like this?

Paul B. Preciado: You are right; I have also written about it in Libération. I am worried, truly worried, about what is happening… and the predominant way the Western media talks about it is also terrible. And once again, it is an identity problem, and we must not separate things but see the connection: we are killing each other over issues related to identity and territorial possessions, and if we fail to stop this time, I believe everything will be more complex than the “simple” (you understand what I mean) Israeli-Palestinian conflict. If all democracies do not take part in ending this massacre, everything could collapse very soon. Here, too: this could be the last film festival. Do you understand what I mean? We must defend democracy.

Leonardo Caffo: That is very clear to me. What concerned you, then, while making this film, also in relation to what you just told me?

Paul B. Preciado: To liberate. To liberate ourselves from the violence of imposing identities we did not choose but which condition us: the cultural backgrounds we inherit from the past that, if overcome, are defined as dysphoria or a political attack. This is, for me, the most relevant question of our time, and I believe art could do a great deal… this is why I moved from philosophy to art, from art to cinema… you will have seen it in the film. The most important thing for me is the poetic gaze, the one with which to reincarnate the world and observe things differently. To give them a new form, a different delicacy, an alternative substance to the belligerent and violent language of daily reality. And because, as in my ending, one day we might arrive at a society that no longer divides between males and females, which essentially means leaving the freedom to be whatever one wants. Or the suspicion that there would be far fewer wars, much less pain.

◊ ◊ ◊

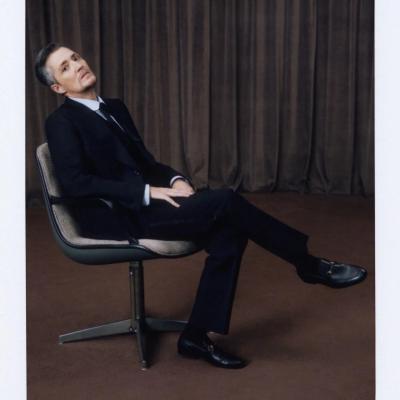

Image supplied by Paul B. Preciado.