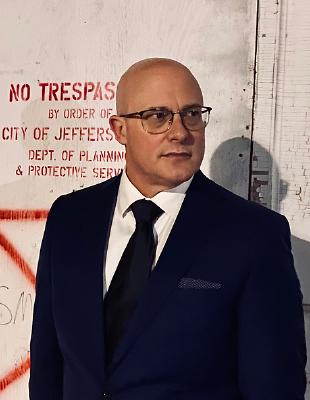

Shane Epting on the Philosophy of Cities

Philosopher interviews

If you like reading about philosophy, here's a free, weekly newsletter with articles just like this one: Send it to me!

I love philosophy, all kinds. When I think about some of the “great works” in the discipline, they remain accessible. I do my best to embrace this quality. I think I get it right sometimes while failing in other instances. Progress, not perfection, as my friends say.

Getting more to your point, I don’t want to tell anyone else how to do philosophy or think. I have a penchant for works that cut from the abstract to the concrete. I recently argued that the academy needs a new kind of philosophy that participates in interdisciplinary conversations. Several contemporary philosophers' works are inherently philosophical while remaining connected to the academy. Grant Silva’s article “Racism as Self-love” is an excellent example. Such papers offer insights into real-world situations, revealing the extraordinary in the ordinary. One way to usher in an age of new philosophy is to encourage people to be their own philosophers. I’m not saying to ignore the canon or relevant works. Dare to use your understanding of philosophy to reflect your personality and genuine interests.

For instance, when working on my Ph.D., my vehicle went kaput. I walked over a mile and rode two buses and a train to get to my university. During my first academic job, I waited in the blistering Mojave Desert sun to catch a bus enough times to burn the experience into my memory for life. These lessons guide my research. While I cannot (and do not) speak for others with harsher conditions compounded by racism, classism, sexism, and ableism, I’ve positioned my work to speak against the conditions that perpetuate such harm in general (among other kinds). These points are evident in my first book, The Morality of Urban Mobility: Technology and Philosophy of the City.

There are several ways to think about moral ordering. One way is to see it as an extension of moral extensionism in environmental ethics. For example, environmental ethics addresses issues between humans and nonhumans. When dealing with cities, there are multiple stakeholders (or groups that hold the place as stakeholders, which requires much more fleshing out than I can do in an interview). They include marginalized people, vulnerable populations, the public (including the former groups!), the nonhuman world, (our idea of) possible future generations, and urban artifacts. For some situations in urban environments, a sophisticated issue could require prioritizing which groups receive initial actions and to what degree, is itself a moral issue — the issue of moral prioritization.

Moral ordering is to be done with stakeholders through a process called co-planning. It has the gist of participatory planning but is less hierarchical. The term “participatory” bears a slight negative connotation. It holds that people are allowed to participate. Urban planners give it. But it is not theirs to give. We must plan in concert to have a city. Otherwise, it is a drab urban center that speaks to our lower instincts. Planners, engineers, public health workers, and architects can keep us safe from flooding, fires, and disease, but only the insights of urban dwellers can testify to the outcomes they create. It is disrespectful to plan or maintain a city without including those stakeholders meaningfully.

Your ad-blocker ate the form? Just click here to subscribe!

Some planners think people like me are wasting paper by writing on topics within their domain. The brilliant author Jessie Singer reminds us that there are no accidents in built environments. I can point to pedestrian and bicyclist deaths or any issues wherein people are harmed. Are they willing to take full responsibility? I have also met incredible planners and engineers who understand the severity of urban technologies’ impacts on humankind. They recognize their power to improve urban life, working tirelessly to fight the good fight. From my limited experience, they are willing to listen and engage.

For example, I created a course called Transportation Justice at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. I invited the Regional Planning Manager of the Regional Transportation Commission (RTC) of Southern Nevada to present future planning measures to the class. Some students challenged the ideas, using the course material to illustrate shortcomings. Rather than act defensively or dismissively, they engaged with the students respectfully and appreciatively.

Eugene Hargrove eviscerates ecocentrism in his 1992 paper, “Weak Anthropocentric Intrinsic Value,” published in The Monist. Proponents of “ecocentrism” never could respond. Still, they kept publishing as if their entire approach had not just been destroyed. All subsequent papers that appeal to “ecocentrism” rest on unsound foundations. I refer to this condition as “The Hargrovian Sleeper.” This notion entails that all views employing the term suffer from a smuggled-in defect. Weak anthropocentrism can repair the foundations to get the job done. I advise anyone interested in “ecocentrism” to read this paper.

Weak anthropocentrism is the best device of the mind to accomplish this task because it inherently establishes a fluid hierarchy: humans and nonhumans. Within the “human” grouping, you can make a further distinction for groups requiring it. For moral ordering, groups having “buy-in” (such as suffering from pre-existing unethical conditions) come first.

We cannot avoid seeing the nonhuman world anthropocentrically. Accepting this reality means we would save an island because it is in our interests, even though it involves the nonhuman world. Once people see this view correctly, the issue goes away.

Again, ecocentrism does not exist. Still, it is worth mentioning that moral ordering is a fluid framework. This point suggests that urgent or substantially pressing matters mean that you can move a stakeholder group up the hierarchy when necessary. But, yes, your question exposes a harsh reality. It shows why we cannot always achieve a “universal design.” Understanding the inescapability of anthropocentrism means that we cannot avoid acting for humankind’s interests, no matter how green we think our thinking is. People, including me, love the nonhuman world. My philosophy is one of love, but it is also the quest for attaining an accurate state of affairs. An environmental philosophy aiming to de-center humankind appeals to many. Yet, it is only as sound as it can be epistemologically grounded. For ecocentrism, this ground does not exist.

It is impossible to uproot billions of people to create smaller cities. We must deal with situations that exist. This reason is why moral ordering is a fluid framework. It must be adaptable. Moral ordering provides a way to say that planning cities for cars instead of people is wrong in ways that go beyond emotivism. It shows the multilayered wrongs entailed in such decisions. Rather than merely complaining about things or endlessly working to identify or interpret the problem or the world, it shows us how to change it. Isn’t this last point the neglected enterprise from philosophers?

I’m not a psychic. I hear people say ridiculous things all the time about what is going to happen and why. I ask for evidence. I’m sure some remote work will stay because it benefits the bottom line, not people. On the one hand, I wonder why it is such a strange concept that people should want to be around each other. Working with a good crew is irreplaceable. Students were incredibly excited to return to classrooms. Perhaps the water cooler is not lonely anymore, either.

On the other hand, some people have long commutes, dependents, and unique situations that make working in a specific location troublesome. I’ve had some bosses and coworkers that were a pain to be around (in polite terms). Remote work could alleviate some of these kinds of issues. Plus, working on one’s own schedule is a huge plus.

Jonas’ critique shows that the entire canon of Western ethics is ill-equipped to deal with modern technology’s challenges. It failed to account for the nonhuman world, the conditions required for future people, accumulating effects, and the global impacts of technology (among others). Philosophers who have quickly addressed related matters without reading his work miss the essential wisdom that can guide us to ecological and social salvation. He puts it best: “We need wisdom most when we believe in it the least.” I have no problem employing utilitarianism to help gain insight into an issue, but I do not hold it dearly as some philosophers do.

I argue that Jonas was talking about “genuine” human life in the classical sense. I do criticize him. While I enjoy his insights, I argue that his imperative for technology is too vague to be applicable in many instances. Moral ordering is a way to employ his wisdom.

As for the future, the idea that we are constantly dealing with the present is reality. The propensity to escape having to address current problems is more troubling than neglecting distant ones. Many contemporary authors writing on “the future” fail to do their due diligence. They ignore Jonas' “pre-evisceration” of the idea that we have debts to possible future people. Some analytic philosophers frame it as a version of the non-identity problem. Emilé Torres does a lot of work on these matters.

Focusing exclusively on the future is troubling. Talking about existing problems makes you vulnerable. You could be wrong. This reason is why I have never made any claims about what a group needs unless I belong to that group. Still, I have no issue saying that harm shouldn’t continue or gesturing toward possible avenues for relief.

When dealing with direct action aimed at “the future,” you cannot be wrong. There is always the possibility that you could be correct. It is no wonder that many philosophers talk about future technologies instead of existing ones. Think about the allure, making arguments where you can’t be wrong entirely.

I don’t think the capability approach would be helpful here for more reasons than I care to explain.

You say: “At the end of your book (p.151), you say that we should prioritise the solution of present problems over the anticipation of future problems. But isn’t this arguably what creates the big problems in the long run?”

The quick response is this: why not clean up your mess before making another?

The less-quick-but-still-quick response is this: It ignores the human suffering that exists. Even though we can ease your burdens—from the harms that, in many ways, municipalities caused—we’ll focus on issues lacking urgency in many cases. We cannot predict the future, but we can address current problems. I could not look in the mirror if I were to take that position.

You say, “should we not try to anticipate and take properly into account the long-term consequences of our actions, rather than prioritising the present?”

This question assumes a false dichotomy. It fails to acknowledge that we can look back while looking forward when delivering solutions. Still, harmed and vulnerable groups already have “buy-in,” showing why we must address such issues before moving forward. However, urgent matters can shift prioritization when required. This reason underscores why we must employ a fluid framework. Moral ordering works for us instead of us working for it. Strictly adhering to a framework when it fails sounds like belonging to a cult. I say this as a “recovering deontologist.”

I have no knowledge of such things.

I don’t deal with space. I prefer to discuss land, streets, boulevards, parks, and concrete. One of my goals is to decrease obscurity, especially considering that philosophy is inherently abstract. Your question is better suited for philosophers such as Paula Cristina Pereira at the University of Porto. She specializes in this topic and prefers to call it “common space.”

Cities are where theory meets practice. In one of the first books to philosophically deal with cities in contemporary times, The Philosophy of Urban Existence (1974) by Arthur K. Biermann, he has a great line in the preface: “Lately, I have been anxious to move philosophy out of the academy and into the world, closer to the chaos.”

Philosophy is everywhere in the world. Sor Juana Inez de la Cruz quipped that Aristotle would have learned more if he had spent more time in the kitchen. For our concerns, the city is a philosophical laboratory, and it has much to teach us, from the armchair to the street. For the former, pondering the question, “What is a city?” is an endless enterprise. There are so many answers! People usually start by comparing it to other things.

They end up saying things like, “a city is a …” They fill the blank with words like ecosystem, living organism, work of art, technology, mega-machine, cyborg, process, etc. Most of them are helpful or at least entertaining.

The concept of “urban technology” is fascinating. I consider zoning, building codes, and urban growth boundaries as technologies. The same goes for job titles: mayor, city council member, and dispatch operator. These are technologies of thought we use to get the job done. Participatory Budgeting in New York City is a specific urban technology, a democratic technology. It helps urban dwellers determine which projects to fund to enhance life.

For the streets, there is the distribution of land, resources, and services. Ensuring that they are ethically sustainable is a sophisticated affair. Moral ordering makes such matters manageable. In addition to this business, countless urban issues would benefit from philosophical examination. From political recognition of who gets to participate in such affairs to the design of bus stops and bicycle lanes, topics are not in short supply for investigation. Philosophy of the city needs more researchers to deal with these subjects.

Universities and philosophy departments would be well-served by hiring in this area. Philosophers are incredibly helpful in making sense of complicated projects, especially regarding ethical matters and broader social impacts. Recently, computer scientists and engineers recruited me to work on two grant projects that intersect with my research on cities.

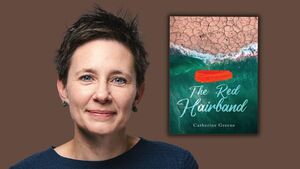

I’ve written three other books since this one. The second, Saving Cities: A Taxonomy of Urban Technologies, is a prequel. It shows how we can extend Heidegger’s thinking on kinds of technologies to account for ones associated with wicked problems such as climate change. I call them “wicked technologies.” Cities, as technologies, are wicked to the extreme. I then explore the mitigatory thought technologies necessary to save us from an anthropogenic demise. I call them “saving technologies.” The third book, Ethics in Agribusiness: Justice and Global Food in Focus, examines the food supply chains that include micro, macro, and meta-level harm. I show that while food logistics could have intrinsic value, we cannot make that claim due to the social and ecological disadvantages of the food trade. If agribusiness is going to reform itself to remedy such effects, we’ll need an enforceable policy backed by a sustainable food label. The fourth is Urban Enlightenment: Multistakeholder Engagement and the City (Routledge, release date: March 10) examines numerous elements of moral ordering and urban enlightenment. It puts forth new requirements on what it means for a city and its citizens to exist. I’ll be on tour promoting the ideas this Spring. My website and social media accounts will have the places and dates.

www.shaneepting.org. They can also find me on Twitter and Instagram.

Thank you!

◊ ◊ ◊