Moral Statements and Truth

1

Suppose you wanted to justify to someone why something is morally wrong. This can be put by saying that you want to justify why the statement of that wrong is true. Let us consider one seemingly uncontroversial (we will come back to that) statement:

(a) Beating up old ladies is morally wrong.

We might even not add ‘morally’ here, as that it is wrong by way of being morally wrong is implied – as opposed to it just being a practical mistake like trying to pour boiling water into an upturned tea mug is wrong if what one wants to do is make a mug of coffee.

Now consider two other statements:

(b) Plants harness the energy from the sun by a chemical photosynthesis.

(c) 2+3=5

Statement (b) is a factual statement. Statement (c) is a mathematical statement.

Taken together, some complication aside, (a), (b) and (c) exhaust all the kinds of statement there are that purport to state truths. (In saying that (a) is taken as sub-class of value statements – other value statements might be aesthetic, for example.) This means that if one does not accept as true these statements, it is supposed, one would be making some kind of mistake, one would not be correct.

2

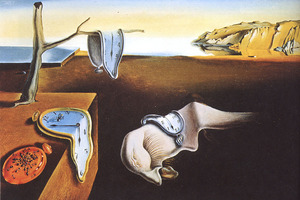

Before getting onto the main issue here, small detour, but one that may occur as a puzzle or objection to the alert reader. Most people would accept that statement (a) uncontroversially states something that is morally wrong, and that the statement conveying this is therefore true. There we are with the picture in our heads of some defenceless old woman being brutally hurt and injured by a pair of heartless thugs as she walks down a street.

In fact it is very hard indeed to think of any particular moral statement that is absolutely and universally wrong, such that it may be stated as true without fear of caveat or qualification. Although we might say, other things being equal, ceteris paribus – that is, in normal or usual circumstances – (a) Beating up old ladies in morally wrong. One could imagine circumstances where one might present a moral justification for it. What if they were nasty old ladies who were keeping a group of young children prisoner and torturing them, but would not, except by beating them up, tell you where they are such that if you did not get to the children they would die? Then one would have to accept the statement as true (a*) Beating up old ladies is sometimes not wrong.

As has been said, it is very hard to think of a moral statement that everyone would accept as true, as expressing a moral wrong, in all circumstances, as a universal absolute. The best stab at it might be something like: Torturing babies is wrong. Even then, is it impossible to think of circumstances where ‘Torturing babies is wrong’ is false, and does not describe a moral wrong? Well, that is perhaps best left to the reader’s imagination. But one may note that in order to turn a moral statement presented as true into watertight absolute truth, taking the babies one as an example, one should not be tempted to state it in the form say, ‘Gratuitously torturing babies is wrong’, because then it becomes a question-begging tautology; in effect saying that torturing babies is wrong if there is no good reason for it.

3

So why is it so hard to know what to say by way of justification that would show that moral statements are true?

Let us contrast moral statements with factual and mathematical statements of truths.

Starting with the factual statement (b) above. One wishes to justify it as true. Well, one would go to scientific literature in which the mechanism of photosynthesis is described and how it applies according to the evidence of what goes on in plants. Now someone might not accept this as sufficient; but this is not what is at stake here; what is at stake is showing the statement to be true regardless of whether anyone is convinced of its truth following the justification given. People are convinced of truth by bad arguments and poor evidence as well as by good arguments and good evidence; whether they are convinced or not is a matter of psychology not of logic or reason. So, nevertheless, if the description of photosynthesis in plants is correct by matching what happens in the world, the statement (b) is true. In short, factual statements are true because they accord with a state of affairs, a fact – what things there are in the world and what they do – and are false otherwise. Now seasoned philosophers will know that understanding what it is for something to be true is more complicated than that. But for the sake of the argument here, that of contrasting moral statements with factual statements, this need not detain us. To put it vaguely even, in the case of factual statements, there is something about the world and how it is that may be referred to that purportedly shows the factual statements to be true.

Contrast the moral statements. In the case of those, such as (a), there appears to be nothing in the world one can point to that is the moral wrongness of beating up old ladies, by which we may show it to be so. There is the beating up of the old ladies – those are facts about something happening in the world, something that may happen or not, that may be true or false – but where is the wrongness? What could one point to? Here is what happened to the poor beleaguered old lady. She is walking along one day down a quiet street, minding her own business, when two young men grab her from behind, start pushing her around, hitting her in face, knocking her to the floor, leaving her with cuts, bruises, and a broken rib. But there is no mention of the moral wrongness of what happened which would entail that it is something that because it is wrong ought not to happen – so that if one behaved as the young men did one would be making a moral mistake. This suggests that moral wrongness cannot, as can facts, be justified and verified as true by pointing to things that happen or do not happen in the world. You cannot show the moral wrongness by piling up facts about the world. Rather it seems that the wrongness of things is a moral judgement that we make upon the facts. But what justifies that?

The main point is that unlike the factual statement about photosynthesis, there are no facts about the world you may just point to that purport to show a moral statement is true, which if true, mean that the moral statement is true.

Your ad-blocker ate the form? Just click here to subscribe!

4

Perhaps in that case moral statements are more like the statements of mathematics or logic. If they do not describe the world in showing what the facts are, perhaps there is some other way of showing that moral statements are true owing to the very nature of the statements themselves. So how do we do that in the case of mathematical truths, such as (c) 2+3=5? What would I do to show someone that mathematical statement – for the sake of argument we will call it that – is true? What would follow from (c) being true is that to hold or assert anything else would be a mistake, would be incorrect. Just as with statement (b) Plants harness the energy from the sun by a chemical photosynthesis, to hold or assert a statement other than (b) would be to make a mistake, would be incorrect. But the way of showing that (c) is true is quite different from the empirical statement about the world (b). The mathematical statement (c) is not a factual statement about the world, though we often roughly treat it like that, for mathematical statements are necessary truths. Factual statements are contingent truths. It might have been the case that plants did not harness the sun by photosynthesis, even if it is in fact true that they do. But there is no possibility of 2+3=5 not being true as a statement of mathematics. The way one usually shows that a statement is a necessary truth is by showing that its denial would be a logical contradiction.

2=1+1, and 3=1+1+1, and 5=1+1+1+1+1, so to assert that 2+3≠5 (that 2+3 is not equal to 5), would be the same as asserting that 1+1+1+1+1≠1+1+1+1+1. This is clearly a logical contradiction. It would be to assert and deny the same thing at the same time. We do not have to look to the world to know that 2+3=5, and insofar as we might apply it to the world, the statement would cease to be a necessary mathematical truth and would become a contingent truth. In fact, the price to be paid for true mathematical and logical statements being necessary is that they tell us nothing about the world at all. Take the logical truth ‘Either it is raining or it is not raining’ – it certainly will not tell you whether you should take your umbrella or not! It is compatible with any state the world is in, all possible facts. The internal form of mathematical statements, their denial involving a contradiction, is what makes them true. So can this be applied to moral statements such as (a) Beating up old ladies is morally wrong? In which case, the statement would not only be true, but necessarily true. This does carry some of our intuitions about moral statements, that they are not just contingent statements dependent for their truth on facts about the world that could have been different, but are in some sense necessary statements, or at least universally true statements, that could not, other things being equal, be false.

Sadly the likening of ethics and its moral statements to mathematics does not work, for there is no logical contradiction involved in denying statement (a). The denial, the opposite, of statement (a**) Beating up old ladies is not wrong, does not involve a logical contradiction. We may still hold that in some sense the statement is false, but it is not false because it has been shown to involve asserting a contradiction, that is it is not asserting and denying the same statement at the same time.

5

From where does the problem arise with moral statements being true? The problem arises from them involving values, in being value statements. If being shown to correspond to the facts or showing something to be a logical contradiction if negated exhausts the ways in which any statements may be true or false, and moral statements are value statements which purport to be true or false, but they neither have facts to correspond to, nor are such that their denial if true is a contradiction it looks as though moral statements therefore are not the kind of statement that is true or false at all. Moral statements appear to be neither factual nor logical statements. When someone puts forward a moral statement, they are not they suppose putting forward a mere matter of personal taste, but rather a statement that has a force such that others should agree to it else they would be wrong, making a mistake, or be incorrect. They are normative in that they imply what we ought and ought not to think and do. This involves proscriptions and prescriptions. Moral value statements involve putting things in some order of worth, significance, or importance. But not in a way that is a matter of mere personal taste. There is a correct saying, that there is no point in arguing about taste – if one person likes bananas or the colour green, it makes no sense to try and show someone who disagrees with you that they are wrong – one simply either likes them or not, it is a matter of fact – there is no route by argument or appeal to the truth that may show them that they are wrong, have made a mistake, or are incorrect, and that really they do or should like bananas or the colour green. But interestingly, as will be seen, when we get to more pervasive features of human life, things that we might disagree on become fewer. Put it this way: it would be one thing for someone to like or not like bananas or the colour green, it would be quite another for them to not like all food or all colours, we would surely think that odd and nonhuman.

Moral values – as do other types of values, such as aesthetic values – and the statements they are expressed in, it seems do not to refer to facts about the world, nor are they determined as true by their mere logical form, but rather express a stance upon, or attitude towards facts. They do so such that they expect if true widespread if not universal assent. They point here is not that people cannot disagree about values, but that there is some sense in which people can be said to be genuinely disagreeing, as they are not over mere matters of taste. It is not a matter therefore of there being moral truths that are necessarily true, or which proposed moral statements are true or false, but rather the important idea is that truth or falsity are in play, so that some may be true and others false. But it is hard as moral statements are neither factual nor logical to see how this can be so.

6

This leaves us with the puzzle of what kind of statements are moral statements. To say that they express mere matters of taste would effectively be the end of morality. No true arguments could ensue. It would be a mere matter of, you think this and I think that – no point in discussing it. To make a moral statement would just be to evince a positive or negative attitude or feeling about something – one that has no normative universalizing authority or force applicable to others such that they could be correct or incorrect. But this is precisely what moral statements supposedly are: they express an attitude, possibly accompanied by a feeling, towards something that demand the assent of others not by coercion but appeal to the truth.

Perhaps however the demand of the assent of others does not appeal to truth, not at least in a direct sense, while not being a matter of personal taste. What one might appeal to is normal human sensibilities giving a truth not determined by merely counting the number of those who agree, but by making some kind of judgements about a morality that are appropriate for human beings as such. After all, we are talking here about human morality and ethics, not that which might be appropriate to ants, or dolphins, or aliens from another planet, who have entirely different forms of life and are physically and mentally quite other than us. David Hume (‘sentiment of humanity’) and Immanuel Kant (‘Categorical Imperative’) proposed a basis for morality in their different ways along these lines – the basis of morality is found in what it is and means to be human, not in facts about the world. The idea is to base the objective force that moral statements appear to involve on a universal intersubjectivity, giving a quasi-objective truth or falsity to moral value statements. An intersection of what is essential to being human: human nature and the human condition. This is perhaps the best we can do. It is also one might argue good enough. For there is no reason why moral statements should be considered absolute universal truths, rather they are all our conditional human moral values, designed as it were for human beings, and they therefore grow from what human beings in their various essential features are like.

It is notable that most philosophical moral thinkers seem to assume what is right and wrong, and try to find a justificatory basis for what they already ‘know’ is true morally. Which suggests a shared default human moral understanding on broader matters at least.

7

Morality, ethics, is made up, a creation by creatures capable of having values, but it is not a fairy story where anything can happen. Morality, ethics, is not constructed on the basis of nothing, but on the way human beings are and their common sensibilities. That gives us the basis for something to argue about. The morality that we have is a human morality. We have enough in common in human nature and human lives that the values we form which present our attitude the world and to ourselves may have some of the authority of truth across all human beings. Our ability to choose our values, and act not just in accord with moral rules, but follow moral rules, makes humans, as far as we know, unique among living creatures. Values exist because we have discriminatory powers of choice as to signification and worth embedded in the kind of creatures we are engaging with the world as we do. It is hard to see what else morality could be if it is meant to aspire to truth and some claim to default universality, while allowing for genuine argumentative disagreement.

Morality is not handed down from on high. It is a human morality for humans made by and for humans. That we may argue is, for a value set or system, including morality, good enough.

◊ ◊ ◊

Dr John Shand is a Visiting Fellow in Philosophy at the Open University. He studied philosophy at the University of Manchester and King’s College, University of Cambridge. He has taught at Cambridge, Manchester and the Open University. The author of numerous articles, reviews, and edited books, his own books include, Arguing Well (London: Routledge, 2000) and Philosophy and Philosophers: An Introduction to Western Philosophy, 2nd edition (London: Routledge, 2014).

Contact information:

- Dr John Shand, The Open University, Walton Hall, Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire, MK7 6AA, United Kingdom.

- https://open.academia.edu/JohnShand

- http://fass.open.ac.uk/philosophy/people

John Shand on Daily Philosophy: