April 25: Happy Birthday, Genetic Engineering!

April 25, 1953: Watson and Crick publish DNA double helix

If you like reading about philosophy, here's a free, weekly newsletter with articles just like this one: Send it to me!

The book and the truth

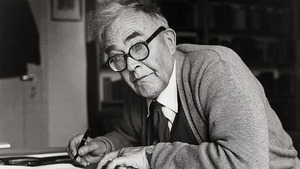

In his book “The Double Helix,” James D. Watson, one of the two scientists who are mainly credited with the discovery, gives a funny, entertaining, sometimes breathtaking, and very memorable account of how he and his colleagues came up with the structure of the DNA molecule. I must have read this book over thirty years ago, and I still have a vivid memory of all the characters and major plot points.

Despite (or perhaps because of) the entertainment that the book is, it has been attacked from many sides. Francis Crick, the other half of the duo who discovered the DNA structure, said (Wikipedia) that the book was just a “contemptible pack of damned nonsense.” This is no wonder when one reads how Watson describes his colleague Crick at the very beginning of the book:

Although Watson acknowledges from the start that the discovery of the DNA had been the work of five people, Maurice Wilkins, Rosalind Franklin, Linus Pauling, Francis Crick, and himself, he goes on to paint his own contribution in a much brighter light than any of the others’. He is especially dismissive of the work of Rosalind Franklin, who was the only woman associated with the discovery, and who, unfortunately, died before she could be awarded a part in the Nobel prize that Watson, Crick and Wilkins shared.

James Watson’s own account of the discovery of the structure of the DNA molecule is an unforgettable science adventure story. Entertaining as much as it is controversial, it should be in the library of any person interested in the history of science.

Amazon affiliate link. If you buy through this link, Daily Philosophy will get a small commission at no cost to you. Thanks!

The scientist and the man

The discovery of the DNA structure led to what we today know as the field of genetic engineering and the ability of human beings to not only identify criminals through DNA tests, but also to detect hereditary diseases before birth, to create new crops that are resistant to diseases or that contain added vitamins and to perform a great number of other miracles.

But it also ushered in a world where we are able to engineer deadly pathogens, where we can make goats produce spider silk, where people can be uniquely fingerprinted from just a few cells, and where we can clone sheep and, almost certainly, also humans.

The man James D. Watson himself is a good example of the two-faced blessings of modern science. A brilliant and demanding scientist, he has, nonetheless, been sorely lacking in common sense and a broader understanding of the world and its issues. He has always been praised for his scientific work, but his thoughts on politics were not more developed than, for example, this 2007 statement: “I turned against the left wing because they don’t like genetics, because genetics implies that sometimes in life we fail because we have bad genes. They want all failure in life to be due to the evil system.” [1] He has voiced similarly deep opinions about “fat people,” women and homosexuals, among other issues. In 2003, he said: “People say it would be terrible if we made all girls pretty. I think it would be great.” (Source: Wikipedia)

Following similar comments on racial issues, some institutions in recent years withdrew the honorary titles they had bestowed on him.

This article is not about James D Watson, but I find that he illustrates well one of the problems of modern science: the extreme specialisation behind every field of study has created an elite of people who are extremely powerful, whose work can be extremely beneficial, but who also often completely lack the ability to understand the world outside of their own little bubble of the scientific universe. Whoever has worked in academia surely knows many such men and women.

Hermann Hesse’s ‘The Glass Bead Game’ may be his greatest novel. It combines a theory of history and education with Zen, and meditations on friendship and duty.

Given the power that science has to change and even to destroy all our lives, we must ask ourselves whether we really want scientists like that (and there are certainly more of them) to be in control of much of our worldwide science — and, in effect, of our common future.

As the German writer Hermann Hesse wrote in his wonderfully deep and intelligent novel “The Glass Bead Game” (German: Das Glasperlenspiel, 1943):

And he goes on to propose that scientists should live in monastic-style communities and devote half their time to science and the other half to meditation and spiritual practices.

A magical vision of a world rebuilt after ours has destroyed itself. Part utopia, part historical treatise, part psychological examination, The Glass Bead Game is a grand adventure in literary imagination.

Amazon affiliate link. If you buy through this link, Daily Philosophy will get a small commission at no cost to you. Thanks!

One is left to wonder whether molecular biology and genetic engineering, together with the rest of our society, would not be better off if they were in the hands of a caste of meditating monks — or whether we have to resign ourselves to a scientific establishment that is led by the kind of people who discovered DNA’s double helix and who now rule our world.

Happy birthday, genetic engineering!

Hermann Hesse’s ‘The Glass Bead Game’ may be his greatest novel. It combines a theory of history and education with Zen, and meditations on friendship and duty.

[1] John H. Richardson. “James Watson - Discovery of DNA structure - James Watson on the Double Helix”. Esquire. Retrieved June 29, 2015. Quoted after Wikipedia.