August 27: Happy Birthday, Human Rights!

August 27, 1789: Declaration of the Rights of the Man and the Citizen

If you like reading about philosophy, here's a free, weekly newsletter with articles just like this one: Send it to me!

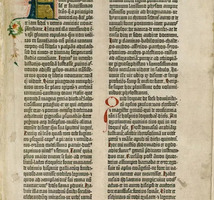

The French Declaration of the Rights of the Man and the Citizen is a remarkable document, not only because its main ideas found their way into many national constitutions and the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

It is also notable as a piece of legislation that was directly derived from an originally philosophical discourse, a thing that doesn’t happen often in human history. But in this transition from theory to practice, the Declaration was conveniently adapted from its lofty philosophical roots to the social reality of its time, losing much of its bite. And so today it remains also notable for being a good example of how philosophical ideas get lost in translation when they are made to serve particular interests in a real-world, political discourse.

The Declaration of the Rights of the Man and the Citizen

The document is not long. Here it is in full (source: Wikipedia):

Article I — Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions can be founded only on the common good.

Article II — The goal of any political association is the conservation of the natural and imprescriptible rights of man. These rights are liberty, property, safety and resistance against oppression.

Article III — The principle of any sovereignty resides essentially in the Nation. No body, no individual can exert authority which does not emanate expressly from it.

Article IV — Liberty consists of doing anything which does not harm others: thus, the exercise of the natural rights of each man has only those borders which assure other members of the society the fruition of these same rights. These borders can be determined only by the law.

Article V — The law has the right to forbid only actions harmful to society. Anything which is not forbidden by the law cannot be impeded, and no one can be constrained to do what it does not order.

Article VI — The law is the expression of the general will. All the citizens have the right of contributing personally or through their representatives to its formation. It must be the same for all, either that it protects, or that it punishes. All the citizens, being equal in its eyes, are equally admissible to all public dignities, places, and employments, according to their capacity and without distinction other than that of their virtues and of their talents.

Article VII — No man can be accused, arrested nor detained but in the cases determined by the law, and according to the forms which it has prescribed. Those who solicit, dispatch, carry out or cause to be carried out arbitrary orders, must be punished; but any citizen called or seized under the terms of the law must obey at once; he renders himself culpable by resistance.

Article VIII — The law should establish only penalties that are strictly and evidently necessary, and no one can be punished but under a law established and promulgated before the offense and legally applied.

Article IX — Any man being presumed innocent until he is declared culpable if it is judged indispensable to arrest him, any rigor which would not be necessary for the securing of his person must be severely reprimanded by the law.

Article X — No one may be disturbed for his opinions, even religious ones, provided that their manifestation does not trouble the public order established by the law.

Article XI — The free communication of thoughts and of opinions is one of the most precious rights of man: any citizen thus may speak, write, print freely, except to respond to the abuse of this liberty, in the cases determined by the law.

Article XII — The guarantee of the rights of man and of the citizen necessitates a public force: this force is thus instituted for the advantage of all and not for the particular utility of those in whom it is trusted.

Article XIII — For the maintenance of the public force and for the expenditures of administration, a common contribution is indispensable; it must be equally distributed to all the citizens, according to their ability to pay.

Article XIV — Each citizen has the right to ascertain, by himself or through his representatives, the need for a public tax, to consent to it freely, to know the uses to which it is put, and of determining the proportion, basis, collection, and duration.

Article XV — The society has the right of requesting an account from any public agent of its administration.

Article XVI — Any society in which the guarantee of rights is not assured, nor the separation of powers determined, has no Constitution.

Article XVII — Property being an inviolable and sacred right, no one can be deprived of private usage, if it is not when the public necessity, legally noted, evidently requires it, and under the condition of a just and prior indemnity.

Men and citizens

The first thing that one notices is the clunky title: Why “the man and the citizen?” Are these two not the same?

It turns out, no. Like the Ancient Greeks, another much admired ‘democracy’ of past times, in 18th century France there were still slaves, and of course these didn’t count as citizens. Neither did women. So this is primarily a declaration of the rights of free, male citizens, rather than all humans. Interestingly, this already contradicts the letter of Article I, which seems to stipulate that _all _men (and, therefore, women and slaves too) are born free and equal in rights.

Interesting also is the second sentence of Article I: “Social distinctions can be founded only on the common good.”

This immediately provides a way out of the requirements of an unconditional equality for all. Yes, we are equal, but only if it does not affect the common good. If the common good requires slavery to exist, or women to stay at home, then this is fine, too. This kind of ‘rubber’ regulation that can be stretched to accommodate almost everything has since become the standard in our legal documents. Everybody is free to do what they want except if it affects others. Black people are equal to white people except if there’s a good reason to treat them differently. And so on. The mere existence of these infinitely stretchable ‘rubber band’ paragraphs makes a farce out of everything that has been said before.

Another example of that is Article X: “No one may be disturbed for his opinions, even religious ones, provided that their manifestation does not trouble the public order established by the law.”

This means that, given a suitable law, people may be ‘disturbed’ for their religious or other opinions. This puts into question the whole point of such a document: a Declaration of Rights (etc) is supposed to be prior to normal government laws, as a state’s constitution limits the range of possible laws that can legally be enacted. But if the Declaration of constitution defers to the normal law, then it has no effect at all. The law itself determines what is right and what is not, and it is, in this case, not constrained by the constitution at all.

August 19: Happy Birthday, Gene Roddenberry!

Gene Roddenberry, creator of Star Trek (August 19, 1921 - October 24, 1991).

Why do we have rights?

Another interesting question is whether there is such a thing as natural and inalienable rights of men. Do men, just by virtue of being biologically members of the species homo sapiens gain particular rights that they cannot ever lose? From the very beginning some philosophers disputed this, most prominently perhaps Jeremy Bentham, the British founder of utilitarianism.

He thought that all rights we have are given to us by law. It makes no sense, so Bentham, to assume that there are somehow, magically rights that have not been given and are not guaranteed by some law, since the only way how rights can ever be claimed is through the social and legal mechanisms that the laws provide. What good is it (or what sense does it make) to claim to ‘have’ a right that one’s society doesn’t recognise? And would this not lead to anarchy and chaos if everyone claimed to ‘have’ such natural rights without having a way to prove that particular rights are given? And how could we ever unambiguously prove the claim that we ‘have’ particular rights by nature alone?

Assuming that rights are given to us by nature would also make it impossible for different people in different societies to claim different rights. Since we all have been homo sapiens sapiens for the past hundred thousand years or so, we must all have had the same natural rights all the time: from the first hunters and gatherers in Africa, all the way through the early empires of Mesopotamia, Greece, Egypt and China, to the Inuit and the indigenous Australian people, to today’s teenagers in the United States. But is this plausible? And what will happen when artificial intelligence systems, in some not so distant future, start interacting intelligently with us? What if we assume for a moment that they even surpass us in intellectual capacity? Should they be unable to claim human rights because they are not homo sapiens?

Like every such document, and like every philosophical theory, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen has its fair share of problems, contradictions and inconsistencies. It has been perverted from the first moment of its existence and reinterpreted to support precisely what it was supposed to oppose: distinctions in rights according to gender and social position. Still, it was a hugely influential first step towards the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Even a bad declaration of rights is surely better than none at all.

Happy Birthday, then, Declaration of Rights of the Man and the Citizen!