Why We Should Read Descartes

In considering this matter I am going to concentrate on the Meditations. Its full title is Meditations on first philosophy. It appeared in 1641. It was a watershed in human intellectual history — not the first, that was Ancient Greece — the kernel of the Enlightenment, and its value is timeless. It is usually regarded as the beginning of what gets termed ‘Modern Philosophy’. But what do these claims mean?

The foundation of knowledge

The overall aim of Descartes’ philosophy is to found science on a secure and absolutely certain footing. Without that anything built by science would be open to doubt following from the weakness of its foundation. The edifice of science could be built, but it would be a tottering ever-fragile tower, each level built on something else, but ultimately infected throughout by whatever uncertainty came from its point of departure.

By ‘science,’ here in Descartes’ view, is meant an objective conception of reality. In order to see what the really real is, any view would have to be completely stripped of any contribution derived from its being from a particular point of view and mode of viewing that would distort seeing things as they are in themselves.

In order to attain absolute certainty Descartes devises the Method of Doubt. This is not only a logical exercise, but a psychological course to follow. Many of the things we once thought true turned out to be false, so how can we sift the true from the false, making sure we only end up with truths? The aim of the Method of Doubt is to systematically doubt, that is, positively consider as false anything that may possibly be false. Only in that way can we be sure that what is left is beyond doubt certainly true. Some of the beliefs subject to this doubt may be true, but that does not matter: if they may be considered false then they are thought of as false.

Having found through the Method of Doubt something that cannot possibly be other than true, that must be true, from the content of that truth Descartes then climbs back up from the vanishing point of what is certain, to show how other beliefs that we think of as true are indeed true and traceably well-founded on something that it is impossible could not be true.

Trying to look for something certain, from which may be derived other views built on that certainty, is not something so unusual in philosophy, but Descartes pursues it with a ruthless rigour not seen before.

That, however, is not what makes Descartes the watershed-radical philosopher he is. Descartes is, in a sense, the founder of the predominant ways of thinking, however varied they became, that followed him, something that led to what we may think of as the mindset of the modern world: that it is incumbent on the individual to think things through for themselves and not just accept what they are told.

What is different about Descartes is that this attitude is personal, egocentric. What can I regard as certain? What can I really know to be true? This at a stroke sets aside all authorities, things you’ve read, and have been told are true, things that you have been told to regard as true and indeed often as certainly true, where doubt would not only be a mistake but quite often would be judged as heinous, scandalous and unthinkable. All the accumulated beliefs of the ages are swept away in one go and instantly.

So Descartes looks only into the content of his own mind for the indubitable truth on which all others can be founded. Purposely personifying this, so that the reader too can go through the same process and not take his word for its validity and for what is indubitably true — for otherwise he would be setting himself as one of those authorities he rejects — he asks us to picture him sitting by the stove actually thinking it through. Don’t just believe him, don’t abstractly accept the process, let alone the result, but actually do it for yourself. Look into your mind with a determination to find only that which is impossible to doubt, that which is impossible to be anything but true. Clear all the clutter away.

He does this in stages, as a strategy, and asks the reader to do the same. It is meant to really help people doubt that which might possibly be false.

Sense perception goes first, how the world appears to us. Not only have we been misled by illusions in particular cases, believing things true that are false, we are often deceived as a whole, as when we take dreams for reality. And there is no way for him to know that even as he engages in the Method of Doubt he is not in fact asleep and dreaming that the world exists. The whole world may not exist as it appears to the senses or at all.

Next goes, perhaps surprisingly, as they are usually regarded as bastions of necessity and certainty, mathematical truths. It’s difficult to see how one can actually doubt that 2+2=4. So perhaps we’ve reached the foundation already. But for Descartes this isn’t good enough, as not only can I make mistakes in mathematics, he also goes on to posit a powerful Evil Genius whose sole job is to deceive us into believing true things that are false.

Again, this is all part of a psychological process of thinking that Descartes wants each of us personally to go through. One should really doubt beliefs that could possibly be false, rather than merely externally viewing the process and considering such beliefs as possibly false only for the sake of argument.

Descartes does not want you to accept his word for where thoughts go and end up. 2+2=4 is a necessary truth, not even the Evil Genius (indeed not even God) can make 2+2=5. So surely then 2+2=4 is precisely the kind of rock-solid certain truth we have been looking for? But not so. The Evil Genius may not be able to make 2+2=5, but he has the power to make us believe that 2+2=5. So mathematics falls to doubt too.

All those things we might consider true derived from experience, the a posteriori truths, are gone, as are all the truths that we might consider as the a priori truths of mathematics. Our minds are emptied.

So what are we left with? What is left is that which we cannot consider false, and even the powerful Evil Genius could not, no matter how much he twists and turns and manipulates our minds, make us consider true when it is false. Again, it is a mental path you can and must take yourself, otherwise the whole point of the method would be self-contradictory as you’d just be taking Descartes’ word for it.

Descartes says that what you will find is that the fact that you are thinking is beyond all possible doubt. No matter how much you doubt, or how fiercely and systematically you do so, no matter how much the Evil Genius throws what are falsehoods in your path as truths, you cannot doubt that you are thinking, for even in the very act of doubting itself, of considering things as true or false, what remains as an absolutely certain truth is that you are thinking. We cannot be deceived into thinking that we are not thinking, because this would again involve thinking.

This short primer explores René Descartes’ Meditations on First Philosophy, his contribution to rationalism, and his impact on early modern philosophy.

He then takes one more step. If he is thinking, he must exist, for as thinking is going on, then the thing that thinks must exist: Cogito Ergo Sum. I think, therefore I am. The most famous motif in all philosophy. This he cannot doubt as true, and you cannot doubt as true, as you’ll find out if you go through the same process as he does: that there is at least one thinking being that exists in the world and that this thinking being is yourself. Now we have reached the absolute foundation.

Restoring the world of truths

After this Descartes builds back from the nature of thinking, the Cogito, the recognisable world of truths. He does this ultimately by a proof of the existence of God derived from the greater reality of something being actual than from it being thought, and that therefore if God is thinkable he must be actual, as otherwise he would not be as great as he could be, and God has all attributes that accrue to Him in the greatest degree.

In short, an imagined God means there must be an actual God existing. Then Descartes moves on to saying that God being the kind of being He is, He would not allow us to be deceived into believing false that which we ‘clearly and distinctly’ believe as true.

And so the edifice of knowledge is restored, but much changed from before, for only things qualifying as clear and distinct ideas may be admitted, and this involves only those beliefs undistorted by a mind contributing nothing to what is reflected in it, and so only reflecting things as they are.

We may say, and rightly, that what follows the Cogito, is itself subject to argument and doubt. However, what we must take from Descartes, considered as a turning point in human thought, is the radical personalization of knowledge. This is his greatest legacy.

Others followed. For example, Locke says that everyone has a duty to make ideas their own. Hume similarly asks us to look into our minds and note what is really there and not go beyond what may be truly inferred from it.

Response to Descartes

So has Descartes had it all his own way? Is he triumphant as to the only way to do philosophy, to set about thinking in the deepest way? His influence is enormous and almost impossible to shake off. Doubts have been expressed about what the Cogito can show, what kind of claim it is, its logical status, the validity of what might be the inference it involves, whether it is entitled to the ‘I’ he infers, and there are long complex works debating that.

But the search for foundations has certainly continued for many philosophers, and even those who reject foundations, like Hegel and Nietzsche, to pick two very different philosophers, are reacting actively against the concept of a foundation because it can’t be achieved.

But there is another way. This is to suggest that Descartes started in the wrong place. It’s not that foundations can’t be achieved, it’s that the very idea of such foundations is misconceived. It is precisely the mental personal aspect of his philosophy such critics object to. They argue that we are already thrown in the world, in it as embodied engaged limited creatures, bumping up against things and dealing with them, and that without this the concepts and thoughts that Descartes helps himself to would not arise at all in his mind. So his starting point of cutting himself off from the world uses concepts in the process of thinking that could not arise from such a cut off position.

Yet Descartes goes on to use them in the process of radical doubt, one that would mean we would not have those concepts in our minds at all and so are not entitled to use them. The necessary contingency of our mode of existence, of engaging with the world, means that an absolutely objective disinterested conception of the world, a view from nowhere, is not possible because it is no view all — to have a view you have to have an interested point of view. And those philosophers who take this line are Heidegger, Sartre, Merleau-Ponty, Wittgenstein, and more recently Richard Rorty. But that’s another story.

We are however left with Descartes as the founder of modern philosophy, the founder of the modern world-view, one that pervades not only philosophy, but all aspects of human life. That will never go away.

After Descartes, human thought will never be the same again. There is no way back to a way of thinking that precedes him once the Cartesian cat is out of the bag, whatever one thinks about it.

And that’s why we should read him.

◊ ◊ ◊

Dr John Shand is a Visiting Fellow in Philosophy at the Open University. He studied philosophy at the University of Manchester and King’s College, University of Cambridge. He has taught at Cambridge, Manchester and the Open University. The author of numerous articles, reviews, and edited books, his own books include, Arguing Well (London: Routledge, 2000) and Philosophy and Philosophers: An Introduction to Western Philosophy, 2nd edition (London: Routledge, 2014).

Contact information:

- Dr John Shand, The Open University, Walton Hall, Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire, MK7 6AA, United Kingdom.

- https://open.academia.edu/JohnShand

- http://fass.open.ac.uk/philosophy/people

John Shand on Daily Philosophy:

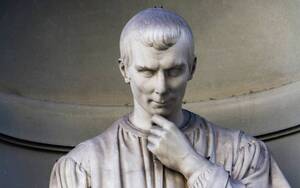

Cover image: Rene Descartes. Frans Hals, c. 1649-1700 AD, Louvre.