The Cicada and the Bird

Chuang Tzu's ancient wisdom translated for modern life

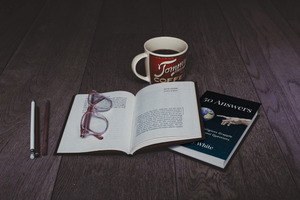

Christopher Tricker (2022). The Cicada and the Bird. The usefulness of a useless philosophy. Chuang Tzu's ancient wisdom translated for modern life.

Amazon affiliate link. If you buy through this link, Daily Philosophy will get a small commission at no cost to you. Thanks!

The following excerpt presents us with Chuang Tzu’s vision of the Tao (the path), and how to walk it. Now, the Tao (the path) means different things to different people. For example, for Confucians it was the path of aristocratic culture and ritual. But for Chuang Tzu, it’s the surface isness (the presenting phenomenology) of things: the shape, colour, texture, and feel of things that we experience directly when we put our brain’s labels aside. His best metaphor for how to walk this path is a story about a cook carving up an ox.

The Cook and the Ox

The cook is unravelling an ox for Cultured Benevolent Lord.

His hand, a subtle turn –

The shoulder leaning just so.

His foot: poised, placed –

The knee bending in flow.

Then whoosh!

Whirl!

Knife suspended –

And swoosh!

Not a sound not in tune.

In time with the Mulberry-Grove Dance.

In step with the Sacred-Chiefs Corroboree.

Cultured Benevolent Lord says:

O, bravo!

How does skill arrive at this?

The cook, putting the knife down, replies:

What your subject cares about is the path.

He’s moved on from skill.

When your subject first began unravelling oxen, he had eyes only for oxen.

After three years, he never attempted to see a whole ox.

And now, your subject meets the parts with his daemon and doesn’t scrutinise them with his eyes.

His administrative thinking stops and his daemon’s longing goes forth,

yielding to the natural grain,

striking at large gaps,

guiding through large openings,

going by the given structure.

To skilfully pass through a joint – that’s something he never attempts, much less a large bone!

Good cooks replace their knife every year, because they cut.

Common cooks replace their knife every month, because they hack.

Well, your subject’s knife is nineteen years old. It has unravelled several thousand oxen and its edge is as if freshly issued from the grindstone.

The sections have space between them, and the knife-edge lacks thickness.

Using something that lacks thickness to enter where there’s space – one’s scope in which to wander is vast. Indeed, the knife has room to spare.

That’s why after nineteen years the knife-edge is as if freshly issued from the grindstone.

Still, when I come across a knot, I see the difficulty it presents.

Warily, cautioned – my gaze stilled; my action slowed – I move the knife ever so subtly.

And poof! The knot unravels itself like a clod of soil crumbling to the ground.

Lowering the knife and straightening up I’ll look around, at a loss for the cause of it.

My intention fulfilled, I wipe the knife and put it away.

Cultured Benevolent Lord says:

Marvellous! I’ve heard the cook’s words and learned from them how to nourish life.

◊ ◊ ◊

This is a comic scene.

In Chuang Tzu’s day a lord would never be seen down in the kitchen. Kitchens were not the chic places of celebrity chefs that they are today. Kitchens were grimy sweathouses of slaughter and blood. When the Confucian philosopher Mencius said, A noble person stays away from the kitchen, he wasn’t poking fun at the noble person’s fragile sensibilities. He was praising the noble person’s gentle and benevolent nature. He was saying that we should stay away from the kitchen. And it’s not that he was opposed to killing animals. Mencius was up for eating a steak or sacrificing a goat. He simply thought that while butchery is an appropriate activity for lowly folk, it is not an appropriate activity for a noble person, a sage.

Chuang Tzu laughs at this moral cowardice and snobbish hypocrisy. He steps square into the reality of life and says, The butchery of the kitchen is the very place where the sage resides.

Chuang Tzu elevates this most lowly and brutal of life’s tasks to the status of high art. Cultured Benevolent Lord describes the cook’s bloody work as an exquisite dance performance. (His hand a subtle turn. The shoulder leaning just so. Etc.) By linking the cook’s movements with the Mulberry-Grove Dance and Sacred-Chiefs Corroboree – two ancient politico-religious ceremonies – he’s saying that the cook’s acts are acts of sacred ceremony that bring about good order in the world.

◊

This story is not about a cook carving up an ox.

The cook’s knife has unravelled thousands of oxen over a period of nineteen years, and is still as sharp as if freshly issued from the grindstone. Its edge isn’t just sharp, it lacks thickness all together. It never makes contact with the meat, but only ever enters the space between the sections of meat. This is not an actual knife or an actual ox. It’s a metaphorical knife and a metaphorical ox.

The ox is a situation. (Think of a situation, a problem, you’re dealing with. This situation is your ox.)

The knife-edge that lacks thickness is awareness that lacks ego: a state of mind in which you are no longer identifying with your brain’s labels and agendas. (You have let your administrative thinking stop.)

When we approach situations with egoless awareness, we can navigate them calmly, allowing them to unravel along their natural seams, knowing that this unravelling is nourishing.

◊

Unravelling problems.

The way to unravel (solve) a problem is to locate the space between its parts, occupy that space, and then let the parts unravel (fall apart).

◊

Seeing the space between the parts.

Our brain’s labels and agendas are like cookie cutters: simplistic shapes that we impose onto things. To see things directly, in all their complexity and nuance, put your brain’s words aside (let your administrative thinking stop). In silence, observe the given structure of the situation (its natural grain). You will see that it is made up of parts, and that there is space between the parts.

◊

Letting your daemon’s longing enter the space between the parts.

Your daemon’s longing is your felt sense of aliveness, your felt inclinations, urges, promptings.

So, with your brain’s words off to the side –

With the given structure of the situation clear before you –

Feel your way into the space between the parts. Allow your response to emerge.

In a difficult situation, slow right down. Take care that your brain, your administrative thinking, does not hijack your awareness and start hacking at the difficulty.

◊

The cook’s intention is fulfilled.

When you identify with your administrative thinking (your brain’s labels and agendas), your intention is a specific outcome. Hacking away at things, sometimes you get the cut you want, sometimes you don’t.

When your intention is to unravel the situation, your intention is that the situation unravels along its natural seams. With this intention your intention is always fulfilled.

◊

But if you want a specific thing, why not hack?

To get a specific cut of meat, good cooks and common cooks hack at the oxen of the world – and their knives blunt. We’re all familiar with this blunted knife. Weariness. Frustration. Despair.

◊

Unravelled situations are nourishing.

An unravelled ox nourishes the people it feeds.

An unravelled situation nourishes the process of life.

The things we now love and cling to are the products of unravelled oxen, of once whole situations that broke apart and thus fed the current situation.

Situations rarely unravel in the way that we intend or want up front. Situations unravel in unplanned, unexpected, undesired ways. But if we allow them to unravel, they will nourish us.

◊ ◊ ◊

Notes

Chuang Tzu. Often written ‘Zhuangzi’. ‘Chuang Tzu’ is the Wade-Giles romanisation, which was the main transliteration used in the 20th century. ‘Zhuangzi’ is the Pinyin romanisation, which is the almost universally used transliteration nowadays. I use the now out-of-date Wade-Giles spelling because ‘Chuang Tzu’ is rounded, warm, and conveys a sense of Eastern antiquity. ‘Zhuangzi’ is a harsh neon-lit nightmare of futuristic zeds.

Cultured Benevolent Lord. This name is a posthumous title, a respectful title drawn from a stock list. Chuang Tzu has chosen this title intentionally: he is comically putting a cultured and benevolent lord down in the grimy, brutal kitchen.

Christopher Tricker (2022). The Cicada and the Bird. The usefulness of a useless philosophy. Chuang Tzu's ancient wisdom translated for modern life.

Amazon affiliate link. If you buy through this link, Daily Philosophy will get a small commission at no cost to you. Thanks!

◊ ◊ ◊

Christopher Tricker is an independent writer who taught himself Classical Chinese so that he could find out what Chuang Tzu says. His edition and translation of Chuang Tzu’s long-lost book is published as The Cicada and The Bird. The Usefulness of a Useless Philosophy. Chuang Tzu’s Ancient Wisdom Translated for Modern Life (2022).

Christopher practices psychotherapy in the Northern Rivers, New South Wales, Australia.

Contact: pathapprover@gmail.com

Christopher Tricker on Daily Philosophy: