Who Gets the Vaccine First?

Philosopher John Rawls on justice and privilege

If you like reading about philosophy, here's a free, weekly newsletter with articles just like this one: Send it to me!

This is the second part of a three part series on the ethics of vaccinations. If you missed the first part, it is here:

Vaccination ethics is a surprisingly rich field of philosophical inquiry, and it covers issues from all major moral theories, reaching into world politics, poverty, the role of the state and the morality of taxation and car seat belts.

In the previous article in this three-part series, we talked about the ethics of vaccines, and particularly about whether the state has an obligation to care for our safety. If so, how far does this obligation go? What right does the state have to force me, possibly against my will, to do what is good for me? If you missed that article, you might want to go back and have a look at it now.

Today, we want to go from the relationship of a state to its citizens to the question of justice between states.

A vaccine, especially a newly developed one for a global pandemic, is naturally a much-demanded but limited resource. Our world is, for the most part, capitalist, driven by the basic economics of demand and supply, and vaccines are no exception. If states don’t interfere by subsidising the distribution of vaccines (or otherwise force the manufacturers to part with them for less than their real value), the price of vaccines will rise until they are available only to the wealthier states and individuals. A large majority of less privileged people around the world will be left without access to the vaccine, and this then poses the ethical question: how are we supposed to regulate access to life-saving medical procedures for those who cannot afford the free market price?

Various answers are possible.

How could states approach unequal vaccine distribution?

First, we could accept the status quo in which rich countries and individuals have access to the vaccine and poorer ones don’t. This doesn’t seem particularly moral, though. Utilitarianism would ask whether this option maximises the welfare and happiness for all concerned parties. Since in any population the rich are fewer than the poor, reserving vital resources for the exclusive use of the rich cannot maximise the sum of happiness among all stakeholders. Therefore, utilitarianism would reject this approach.

Utilitarianism is a moral theory that states that the morally right action maximizes happiness or benefit and minimizes pain or harm for all stakeholders. Proponents of classic utilitarianism are Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) and John Stuart Mill (1806-1873).

For Kant, it is important that all human beings are treated as ends in themselves; this means, as people who are equally valuable as every other person. In this view, nobody is more valuable than anyone else. Not making the vaccine available to the poor would treat them as second-class citizens, which would violate Kant’s imperative that they should be treated as ends.

Second, we could ask the richer countries to subsidise the vaccination of poorer ones through some kind of vaccine-sharing or state-aid scheme. But why would the wealthier countries agree to such a scheme? Again, various models are possible, some involving exchange of some other commodity, some based on altruism, and perhaps some based on other considerations that make such aid seem rational to the sponsoring country. For example, one could argue that the whole world would be better off if the virus could be eradicated. Not only would international travel and commerce work better and more efficiently; healthy and happy populations in the world’s poorer areas would also reduce the incentive for migration and perhaps help avoid armed conflicts over resources in these countries. In the long run, the political stability gained in this way might be worth a lot more than the cost of a few billion doses of a vaccine.

Kant’s ethics is based on the value of one’s motivation and two so-called Categorical Imperatives, or general rules that must apply to every action.

Third, the countries who host the production facilities for the vaccine could, in some way, take control of the production facilities, either by forcibly nationalising them, or by making long-term agreements with the manufacturer that would arrange for some kind of compensation later on. We talked last time about the social contract theory. For Locke and Rousseau, the state’s primary function is to protect the citizens, and Locke specifically mentions private property as one important good that the state is supposed to safeguard. So the forced nationalisation of production facilities would not be something that Locke would agree to. Generally, the social contract theory would look at what kinds of agreements rational agents would agree to freely. A promise of long-term compensation in exchange for access to the vaccine might be something that the vaccine’s manufacturer might rationally agree to, and so this approach would be morally right.

John Rawls: Original position and the veil of ignorance

One of the most important and influential theories of justice has been proposed by US philosopher John Rawls (1921-2002) in his book “A Theory of Justice” (1971).

The basic idea of Rawls is that, in order to make just choices, we should imagine ourselves as being in this world, but not being ourselves as we are now. Instead, try to imagine you are conscious before you are actually born as a particular individual. Perhaps like we would imagine a soul that is waiting to be born into a human body — it is already there, waiting, but it doesn’t know in which body it will eventually end up (the wacky explanation is mine, not Rawls’). This situation Rawls calls the “original position.” This is the point at which we are able to make decisions, but we are not yet committed to a particular camp, to a particular nation, a gender, a religion, a social class, a family, a body. In the uncertainty of this original position, it seems equally likely that we will be born as a farmer in India, a businessman in Shanghai, a mother of seven in rural Alaska, or a war orphan in Syria.

In this situation now, imagine that you’re looking down on Earth, trying to create rules for a just society, not knowing as who of all those people down there you will eventually be born. This “not-knowing” Rawls calls the “veil of ignorance”. This veil is like a curtain that hides the (future) reality from your view.

Rawls believes that if we create rules and laws in this way, we are more likely to create a truly just society than if we do it from our present perspective as the person we happened to be born as.

Your ad-blocker ate the form? Just click here to subscribe!

Rawls’ two principles of justice

From this original position, Rawls thinks, we would arrive at the following three principles of justice (he speaks of two, but the second has two parts, so somehow it seems clearer to say that there are really three of them):

The Liberty Principle. All citizens should have equal basic liberties: freedom of conscience, association, expression and personal property.

The Fair Equality of Opportunity. Offices and positions should be open and effectively accessible to all. (It’s interesting to compare this to Nussbaum’s concept of capabilities).

The Difference Principle. Any inequalities are only permitted if they work to the advantage of the least well-off.

Let’s now briefly think how we can apply these principles to international vaccine distribution.

When we think about how to regulate vaccine access, we should do so from “behind the veil,” that is, assuming that we don’t yet know as who we will be born on this Earth. So you wouldn’t try to regulate vaccine access knowing that you are a German teacher, an Indian programmer, a US farmer, or a Japanese monk. Instead, you would assume that you might be in any of these roles, having to deal with the consequences of your regulation.

And the crucial question is: How would you regulate then?

Rawls’s book A Theory of Justice is one of the most important books of the 20th century in the philosophy of justice and law.

Amazon affiliate link. If you buy through this link, Daily Philosophy will get a small commission at no cost to you. Thanks!

Vaccinations and the Liberty Principle

Rawls’ first principle is about equal basic liberties for all citizens: freedom of conscience, association, expression and personal property. Applied to the vaccine question, we see that basic access to healthcare is a necessary condition for most of the other liberties. What good is my freedom of expression if I’m dead from the virus? Of course, there is also a conflict here: What should happen if someone does not want to be vaccinated? On the one hand, we want to respect their liberty. But on the other hand, exercising their liberty will make it more likely that they will endanger others by transmitting the virus to them.

It is here also important to note that the anti-vaxxers cannot argue that the vaccinated people are, well, vaccinated, and so they shouldn’t care any more whether the virus circulates among the non-vaccinated or not. It is still relevant to all of society whether the virus is in circulation or not, because viruses mutate while they are transmitted around a population, and every mutation brings with it some probability that the virus will acquire the ability to infect even those who have been vaccinated. So it is indeed important to the vaccinated, for their own safety, to not have anti-vaxxers in their community because these may be hosting and propagating the virus among them, giving it opportunities to mutate and overcome the protection of the vaccine.

So here the liberty and personal safety of the vaccinated is in a direct conflict with the liberty of the vaccination opponents. We will talk more about this point later on. It is just something to notice about Rawls’ theory. Basic liberties always tend to be in conflict with each other: one person’s liberty to carry a gun conflicts with another person’s preference to live in a safe city without shootings. Honoring the principle of liberty is never going to be easy.

Fair Equality of Opportunity

According to Rawls, offices and positions should be open and effectively accessible to all. In terms of vaccinations, we might understand this to mean that access to the vaccine (and therefore affordable healthcare) should be available equally to all. It cannot only be a privilege of rich countries, or rich citizens within a country.

The Difference Principle

Any inequalities are only permitted if they work to the advantage of the least well-off.

This principle breaks the symmetry of the previous one. If we need to distribute vaccines unequally, perhaps because not enough are available at a given moment, we should always restrict in favour of the poorer, least well-off countries and individuals. That means, richer countries and individuals, who have more resources to combat the virus and to recover in the case of an infection, should prioritise giving the vaccine to those who don’t have the same high-quality medical infrastructure available in their countries.

Why should we do that? Why should we give the advantage to the least well-off? For Rawls, this is not “being nice” or anything like that. It is the rational result of creating these rules in the original position, behind one’s veil of ignorance. If you didn’t know whether you will be born as Bill Gates or a farmer in Syria, but you had to make a rule to make the vaccine available first to one of the two: who would it be?

Martha Nussbaum and the Capabilities Approach

In the capabilities approach, philosopher Martha Nussbaum argues that a human life, in order to reach its highest potential, must include a number of “capabilities” – that is, of actual possibilities that one can realise in one’s life.

Obviously, if you were to be Bill Gates, you would be able to take care of yourself, even without the vaccine. But as the farmer in Syria, you might have no way to survive an infection. So assuming I really didn’t know who of these two will be my next incarnation, it would be perfectly rational to give access to the vaccine to the Syrian farmer first. (Bill Gates is just a name here; I am aware that he is a great philanthropist and much more generous with his wealth than most of the others who have amassed similar fortunes).

And that’s the end of today’s article. We began with the question of how we should distribute a scarce vaccine among countries or individuals of different financial means. And we saw that the problem is not easy — but if we commit to Rawls’ assumptions, then it seems that we would not only have to agree to share the vaccine with those who are less wealthy; we would, in fact, have to prioritise them.

◊ ◊ ◊

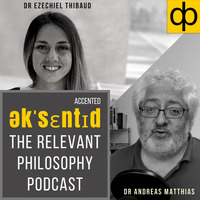

Andreas Matthias on Daily Philosophy: