Books that Lead You to Philosophy

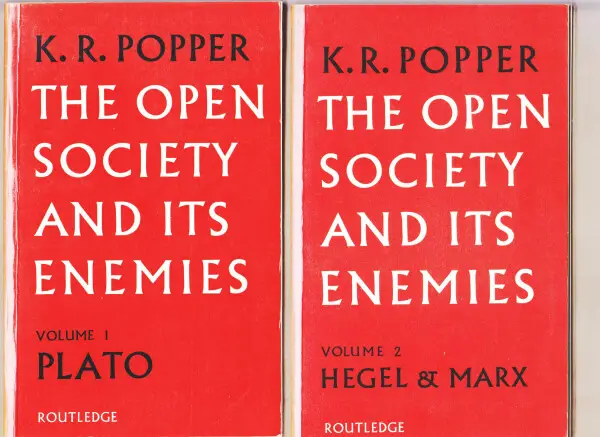

Karl Popper: The Open Society and Its Enemies

The main idea of this essay is not the uninteresting autobiographical one of telling people what led me to philosophy, but rather to pass on what it was so that it might just lead others. There might have been one or two other seminal books I could have chosen.1 At the early stages of getting to know anything where one starts is likely to be happenchance and based on the accident of circumstance. (In this case it just happened to be one of the very few philosophy books in the local public library.) For it is only after one starts that one’s investigations become more directed. You have to be somewhere before you can start finding your way around, wherever that somewhere is.

The book in question is Karl Popper, The Open Society and Its Enemies, first published in 1945.

I shall not go through the details of the discussions of the central protagonists, Plato, Aristotle, Hegel, and Marx, but rather try to convey what lies at the heart of book, the thrust of its argument, and how this opens out into the wider world of philosophy, not so much in the sense of other philosophical subjects, but rather what is at the core of philosophy overall.

Karl Popper, The Open Society and Its Enemies. Buy it right here!

Amazon affiliate link. If you buy through this link, Daily Philosophy will get a small commission at no cost to you. Thanks!

Central to The Open Society and Its Enemies is the advocation of free open critical thought, and an attack on closed finished outlooks that purport to deliver definitive even final answers, both in itself, but also because it is the only that way things can be tried out and errors be corrected. Always keep the door ajar on other views. Keep the running thread of fallibilism in your thoughts – that always you might be wrong, that evidence or arguments may appear that can and should change your mind. The book opposes what it calls tribalism, the closed society. That is, the huddling together behind closed-wall unassailable beliefs, and thereby often setting them up in opposition and conflict to other tribes. This applies to social doctrines on how society should be organised, and the avoiding of all-time right answers.

If one has to intervene as a state in the lives of people, do it in a small-scale piecemeal way, for only then will one have the chance to correct a theoretical idea by trial and error when confronted, as it certainly will be, by the reality of application. Theory always falls short of practice. Eschew grand plans, the radical ripping up from the foundations, the sweeping away and starting again. The results will be a litany of fanning out unintended consequences that are not only harmful or disastrous, but also may be irreversible. We simply do not have and never will have the knowledge for such plans faced as they will be with the stratospheric complexity of human life and human society.2 The attempt is culpably intellectually hubristic. Democracy is the best mechanism for piecemeal plans and change, for only it as a political system allows for change without violence, usually in response to the actual circumstances as they unfold, as well as providing the only legitimacy that a state can have, which in the end always comes down to the legitimacy of someone telling someone else what to do. The idea that we can have a good grasp of the direction society will and should take – historicism - is fatally flawed, not only for the reason of complexity already mentioned, but because of the necessity of the inability to know future knowledge.

Imagine two even modestly separated dates in time, say someone in 1850 trying to draw up plans for how society as a whole should be run, organized, what it should and should not be like and produce in 1950. Think of how hopelessly, possibly laughably, askew it would be given the changes in knowledge and its technological associates. Where would be the saddle makers, the candle makers, the extension of political representation, the use of electricity, the rise of secularism, the start of electronic computers, radio, and the rest?

How then does all this lead to philosophy? It leads by way of raising the matter of becoming questioning and not accepting things on mere authority, no matter how grand and ancient. It leads to thinking for yourself, and learning how to think for yourself well. So that you are not fooled and drawn into a tribe. It’s a life’s work, one should note.

Philosophy is in a sense not just another subject, but the foundation or background of all other subjects, for it involves in its essence thinking things through from the base. Other subjects reply on assumptions about what for example good evidence is, what it is for something to be true, when one is warranted in granting belief to something, what justifies you choosing to act one way rather than another morally, and other fundamental matters, without which those other subjects would be unable to function. Philosophy addresses and values these matters and proposes by way of defensible argument positions one may rationally take on them.

Not everyone likes this to-the-base way of thinking, or even finds it interesting – some might prefer to cocoon themselves in a belief system. However, in preferring closed systems of thought there is the danger of being swept up in some highly seductive movement that in fact turns out to be damaging, that one should, if one had stepped aside and thought harder, have backed away from. But if you do like open-minded free questioning thought looking at the fundamentals of what and how we come to believe things, and should, albeit with the proviso of the possibility of changing our mind, think things true or false, then you should perhaps do some philosophy.

In short, philosophy is what happens when you start to think for yourself with no holds barred. For what is at issue here is not so much what you believe, but rather the way you believe it. Is the belief held by a kind of commitment or faith, even if it is in a quasi-way? – and in some cases the very holding of the belief genuinely is said to be dependent on such unwavering advocation – or is it the best you have in the light of the current arguments and evidence, but one that one might perfectly well change if the arguments or evidence do? It’s not a guarantee against being taken in and taken off by views and ideas – for the determinants of that are often psychological and nonrational and causal (not necessarily irrational, though they may be that too) and not rational – but philosophy done well certainly helps. It is a subject that not only questions beyond itself, but steps back and questions itself too.

It is the excitement and dawning liberation of this kind of thinking, thinking things through yourself, that this is what one can do – and you will know if you have it or not simply by reading it – that The Open Society and Its Enemies can produce, and in that way, it’s on you go finding out what else falls under this way of thinking – in short it leads to philosophy.

◊ ◊ ◊

Dr John Shand is a Visiting Fellow in Philosophy at the Open University. He studied philosophy at the University of Manchester and King’s College, University of Cambridge. He has taught at Cambridge, Manchester and the Open University. The author of numerous articles, reviews, and edited books, his own books include, Arguing Well (London: Routledge, 2000) and Philosophy and Philosophers: An Introduction to Western Philosophy, 2nd edition (London: Routledge, 2014).

Contact information:

- Dr John Shand, The Open University, Walton Hall, Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire, MK7 6AA, United Kingdom.

- https://open.academia.edu/JohnShand

- http://fass.open.ac.uk/philosophy/people

John Shand on Daily Philosophy:

Cover image by Clay Banks on Unsplash.

-

Colin Wilson, The Outsider, (1956). A. J. Ayer, Language, Truth, and Logic (1936). Bertrand Russell, History of Western Philosophy (1945). Someone else will have a different list – there’s nothing definitive about it. ↩︎

-

Karl Popper was acquainted with his fellow Austrian political-economist Frederick Hayek, who throughout his overall liberal economic theory pointed to the impossibility of knowing the preferences and decisions of millions of individuals that make up the bedrock of economic and societal life and reality, that would be required for any large-scale planning to be tenable, effective, or desirable. ↩︎