Immanuel Kant on Means and Ends

Philosophy in Quotes

If you like reading about philosophy, here's a free, weekly newsletter with articles just like this one: Send it to me!

This is a new series, in which we’ll go through the most famous quotes in the history of philosophy! Subscribe here to never miss a post! Find all the articles in the series here.

Immanuel Kant: Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals

”

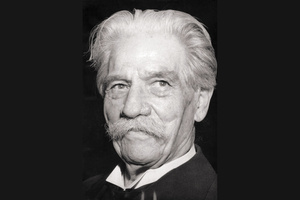

”Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) was one of the most influential philosophers of the past 300 years. Not only that — he was also the embodiment of a philosopher who is too busy with his thoughts to take notice of the actual world.

One of his favourite pastimes was to visit a friend, one Mr Green. Kant would go to Green’s home, only to find him asleep. This happened in the same way every time, without fail. Kant would sit beside Green, waiting for him to wake up. After a while, he would doze off himself. A little later, a third friend would come along and also fall asleep with them, until, finally, the last of the group of friends would enter the room and wake everyone up. Once awake, they had a blast talking about interesting ideas, but only until precisely seven o’clock in the evening. At seven, and not a minute later, the group would break up and everyone would go their own way. The locals, who were used to this weird meeting, would know when it was seven o’clock, because Kant would always pass by the street at exactly this time. 1

Kant needed this kind of regularity and could be profoundly unhappy when something didn’t go according to plan. One time, an acquaintance invited him for a trip to the countryside. But the trip took a bit longer and Kant wasn’t home at his customary bed-time at precisely ten o’clock. This upset him so much that he immediately created a new rule for his life: never to accept another invitation for a trip to the country.

Kant could be charming and witty, his students reported, but he could also do the weirdest things. When his long-time servant, a man named Lampe, left him, he found it very difficult to accustom himself to a life without the man. So he stuck a note to the wall: “Lampe must be forgotten!” One wonders whether the wise man expected this to actually work.

Means and ends

Kant never left his home town, Koenigsberg (today’s Kaliningrad), never married, never changed his daily schedule or his diet, and died, presumably happy and mildly bored, at the age of 80. His last words were: “It’s fine.”

In the course of his long and externally uneventful life, Kant created a series of works that uprooted and changed philosophy for ever. His fundamental Critique of Pure Reason tried to sort out the limits of what we can know independently of all experience of the world; that is, with our “pure reason” alone.

But what we’re interested in today is his ethics. Today, we are accustomed to the thought that all living things have developed out of each other in the long process of natural evolution. We are willing to give rights to animals and to recognise that their concerns are, essentially, of the same importance as our own; their suffering as bad as our own.

But Kant would not entirely agree. He saw that human beings have a particular kind of value that animal lives lack. And this value comes from the ability we have to be autonomous, to decide for ourselves how we want to act and then to actually act upon our decisions.

Animals are caught in the necessities of their instincts. A bee cannot decide to ignore a flower. An ant cannot ignore a morsel of food. A lion cannot freely decide to let a zebra live. And this applies even to those animals that we consider the “highest” on the evolutionary scale, those closest to us: dogs are as much slaves to their instincts as apes. It is only humans, at least this is what Kant believes, who can freely decide which course of action to follow in every situation. Yes, we also have to eat, but many have voluntarily starved to death in hunger strikes, clearly showing that our mind and our free will can triumph over the demands of our bodies. Many are voluntarily celibate. Many abstain from particular foods when dieting. And so on.

This ability we have to act freely, to decide how we want to act, makes us special. Every time we do follow a rule, say a moral rule, we are doing it freely. There is no way to coerce a human being into doing anything. You can punish a murderer, but murders still happen. In principle, we are all free to be murderers, as we are free to be saints. We can decide to be lazy or hard-working. It is always a free decision, no matter which way we choose.

This ability of human beings is what gives them a value that is of a different kind than the value other things have. You can replace one car by another. If you lose a pen, you can buy another. You can go to the market and exchange two eggs for a head of lettuce. And so on.

But one cannot exchange human beings for one another, Kant thinks. You cannot say, I have too many children, so let me exchange two of them for a new car. This would not make sense, and we would immediately recognise such an action as immoral. Why? Because this would implicitly put human beings on the same level as a mere thing, a car. Such an action would deny human beings their special status, what Kant calls their “dignity.”

Wilhelm Weischedel: Die Philosophische Hintertreppe. A very entertaining history of philosophy “through the back door.” Weischedel discusses philosophy through the lives and idiosyncrasies of famous philosophers. Unfortunately, this book seems to be available only in German. If you can read German, it’s very entertaining, wise, and great fun!

Amazon affiliate link. If you buy through this link, Daily Philosophy will get a small commission at no cost to you. Thanks!

Now, what does Kant mean with his talk of “means” and “ends”?

The “end” of an action is what I want to achieve. Let’s say, I want to get my pen back, which I forgot at a friend’s house yesterday. The “means” are the instruments or tools that I will use to get that pen back. I might walk over to my friend’s house to get my pen back, for example. Then my walking there would be the means towards the end of getting my pen back.

But what if my friend lives far away? I can take a taxi. Assuming my pen is worth 5 dollars, and I pay 50 to the taxi to get the pen back: would this be a rational action? No, in this case, I should just use the money directly to buy another pen (or ten of them) instead of trying to retrieve that one pen that I forgot.

So the means that I use to achieve some end must, if I want to be rational, have less value than the end itself.

If humans have a special, unlimited value, it follows that I can never use them as means towards any end. Because no end can have a value that is higher than a human being’s dignity.

Acting in a way that recognises this fact makes sure that we always respect human dignity and that, therefore, we act in a way that is morally right. For Kant, the highest good in acting is to act rationally. And respecting human dignity is a rational necessity. Not doing so would be like paying a 50 dollar taxi bill in order to retrieve a five-dollar pen.

But there is a catch here: if we are not careful, we might interpret this advice as meaning that we can never use a person as means. This would make it impossible to take a bus, for example, because when we do so, we treat the bus driver as a means. Or we could not go to a restaurant, where someone serves us the food, because we would be using this person as means to our food. Clearly, Kant cannot mean that taking a bus or ordering a lunch is immoral.

This is why he has this word “only” in his imperative: “Act so as to treat humanity, whether in your own person or in that of another, at all times also as an end, and not only as a means.”

So we can treat people as means to our ends, as long we do not only treat them as means. For example, I pay the bus driver and the restaurant waiter, and thus I make it possible for them to live their own lives and to pursue their own ends: and this is the way in which I am also treating them as ends.

We don’t necessarily need to pay others in order to treat them as ends. If the other person is your friend, you might from time to time do them a service, listen to their worries, or give them advice. These are all ways to treat others as ends. But if you only use your school “friend” in order to copy his homework, then you are using them as a means only. And this would be wrong.

If we follow Kant’s advice, we will never sacrifice a person for any reason. We will not agree to wars where soldiers get killed for a military gain. We will not accept a prison system that mistreats human beings in the name of deterrence. We will not lie to another just to secure an advantage for ourselves. And we will not exploit workers to lower the prices of our consumer products.

Kant’s “Categorical Imperative,” as this idea is also called, is actually pretty demanding, and it is rightfully considered a kind of gold standard of human behaviour towards others.

Just think how much better our world would be if everyone acted following this quote, if we treated the soldier, the worker, the prisoner, the prostitute, the beggar as ends and not only as means to our own ends:

“Act so as to treat humanity, whether in your own person or in that of another, at all times also as an end, and not only as a means.”

◊ ◊ ◊

Thanks for reading! If you found this article useful, please share it and consider subscribing and supporting Daily Philosophy!

Your ad-blocker ate the form? Just click here to subscribe!

-

The facts on Kant’s personal life were taken from Wilhelm Weischedel’s genius book on the lives of famous philosophers, which, unfortunately, exists only in German. But if you can read German, get it. It’s one of the most entertaining philosophy books: Wilhelm Weischedel, Die Philosophische Hintertreppe. 34 grosse Philosophen in Alltag und Denken. ↩︎