March 28: Thales Predicts a Solar Eclipse

March 28, 585 BC - Really?

If you like reading about philosophy, here's a free, weekly newsletter with articles just like this one: Send it to me!

What’s the date?

Today, I accidentally stumbled upon this entry on Onthisday.com:

Of course, the day wasn’t March 28 for Thales. It would have been some ancient Greek month — but which one? This question led me down a rabbit hole that you are welcome to follow yourself. I’ll put some links at the end of this article and you can meet me right there, at the bottom of the rabbit hole.

First the year: it’s obvious that the Greeks, not knowing the precise future date of the birth of Christ, wouldn’t have named their year 585 BC. But what then?

Turns out, in classic times, they used to count 4-year periods, from one Olympiad to the next. This could work nicely, since the first Olympic Games took place in 776 BC, long before any of the great moments of classic Greek civilisation. Unfortunately, this way of counting the years was only established by a philosopher called Hippias of Elis in the 5th century, and so wouldn’t have been used in 585 BC. I couldn’t find anything about the calendar used in Miletus in Thales’ time, except that it was Thales himself (or, according to some sources, a student of Plato’s academy, Callippus of Cyzicus) who determined that the true length of a year was not 365 days but a quarter of a day more than that. So whatever calendar was in use before and during Thales’ time, would have been increasingly wrong as the years passed, and would have been corrected ad-hoc from time to time, whenever people noticed that it was still snowing in spring.

Photo by Ganapathy Kumar on Unsplash

Ancient Greek calendars

The months were, like in all ancient cultures, aligned with the moon’s phases. In German, even today, the word for “month” is “Monat,” which is related to “Mond,” the word for moon. Unfortunately, the moon’s phases again don’t align with the length of a solar year, so from time to time people dropped a month to make their calendar fit the actual season as they saw it played out in the nature around them.

Let’s not even talk about weeks. The week is a Judeo-Christian concept, derived from the Biblical story of God creating the world in seven days and resting on the last day, which inspired Judeo-Christian-Muslim societies to do the same and declare one day of the week the resting day; depending on the flavour of one’s faith, it would be either the Friday, the Saturday or the Sunday. The ancient Greeks used to divide the month more practically into three ten-day periods, roughly following the phases of the moon throughout its monthly cycle. Except, of course, that the moon doesn’t take thirty days, so right there is another source of misalignment.

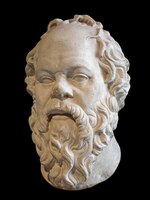

Thales of Miletus is generally cited as one of the first philosophers, although his contributions extended to many sciences and even to business endeavors.

To make things worse, there was a parallel (and probably more common) calendar that farmers used to regulate their activities: the parapegma, which was more like an almanac, assigning particular farming tasks and weather events to corresponding astronomical phenomena. It reads something like this: “Day 28: Aquila sets in the morning. There will be a storm at sea.” (ancient.eu)

The Julian calendar

We had to wait until Julius Caesar, who in 46 BC, five hundred years later, finally brought some order into the calendar. Funnily, we still have remnants of the older Roman calendar in our own languages: the later months of the year, September (latin root sept-: seven), October (eight; compare: octopus, “pous” Greek meaning “foot”), November (nine) and December (Greek deca-: ten) directly tell us of the original position of these months in the old ten-month calendar of the Romans. Caesar just moved them two months ahead, but didn’t change their names.

Even cooler is the fact that in various cultures the new year used to begin at wildly different times. In Alexandria, the year started on August 29. Vladimir of Kiev decreed in 988 that the year would begin on the first of March, while in 1492, Ivan III put it to the first of September. In the European Middle Ages, although the New Year’s day was considered to be the first of January, most countries counted the year from Christmas day (December 25th) or the Incarnation of Jesus on March 25. And if you have read until here, you know now why the fiscal and taxation year in many countries goes from April to March: it’s aligned with the old English year, which from 1155 to 1751 (for almost six hundred years!) began on March 25, the day of the Annunciation, the Incarnation of Christ and (with all the precision the ancients could muster) the spring equinox.

Now the Julian calendar was eventually replaced by the Gregorian calendar, but this didn’t happen at the same time worldwide. Pope Gregory started the Gregorian calendar in 1582, which resulted in nine days never having existed, even for those who switched early. The difference grew to 13 days by 1900, and some countries (Turkey, for example, and Russia) didn’t adopt the new calendar until well into the 20th century.

All this makes it very hard for historians to find out when things actually happened in history. So much so, that there’s a theory that the whole period of almost 300 years, from 614-911 AD, never existed: the phantom time hypothesis.

Thankfully, and now we come back to Thales of Miletus and his eclipse, with eclipses we don’t have all these problems. Eclipses can be precisely predicted by purely mathematical means, and so we know that the one that Thales saw was — probably — the one that happened on what we would today call March 28, 585 BC, and it doesn’t matter a bit what old Thales would have called it.

So there you have it. An hour wasted for nothing :) Have a nice Sunday!

Sources:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Julian_calendar#New_Year’s_Day

- https://www.ancient.eu/article/833/the-athenian-calendar/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eclipse_of_Thales

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phantom_time_hypothesis

- https://www.onthisday.com/date/585bc/may/28