Grateful to No One

How does gratefulness work?

If you like reading about philosophy, here's a free, weekly newsletter with articles just like this one: Send it to me!

This article is part of a series on gratefulness, itself part of a bigger series of trying to live six theories of happiness within the space one year. Click on the links above to get the whole story!

Last week, we began our exploration of gratefulness by distinguishing between gratefulness and gratitude. While gratitude, we said, is the feeling of being thankful to a particular person for a particular (undeserved) benefit, gratefulness is a more general feeling of happiness and thanks towards nobody in particular; as in: “I am grateful for the glorious sunshine.”

It is interesting that in ancient times, the symmetric version of gratitude was the only one that was commonly recognised. Ancient authors write about gratitude generally as a relation between two people, and most of the time about the lack of gratitude as a vice:

Seneca, in his book “On Benefits,” writes:

This is in line with the more general Aristotelian view of human relations. Love, too, is for Aristotle a symmetric relationship, a kind of friendship, in which both partners profit in roughly equal ways by educating each other in matters of virtue and wisdom.

In this mini-series of posts, we trace the history of the concept of love from Plato and Aristotle through the Christian world to the Desert Fathers.

It was Plato who gave us, with his Symposion, the vision of a transcendent, eternal love that can be directed towards things that don’t reciprocate: mathematics, ideas, the eternal forms of perfect things, and God himself. And it was in this Platonic tradition that the later Christian philosophers tried to explore the asymmetries of love and gratitude.

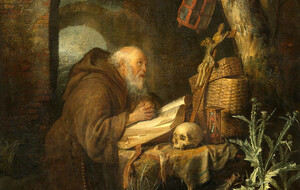

“Gratia,” for St. Augustine (354-430), refers to the grace of God, not to human obligations ([1], p.25). For the Catholic philosopher Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274), gratitude was the appropriate response to receiving a gift; but since the society of the Middle Ages understood itself as a hierarchy of power, from God at the top all the way down to the peasant, such giving and receiving of gifts was also one-directional and ordered according to social status and power. Therefore, gratitude was not the symmetrical Aristotelian version any more. As the Middle Ages had created the asymmetries between God and man, lady and knight, landowner and serf – so also love and gratitude now became directed relations: in love, the knight served his idolised lady with his whole being, just as the monk served God. Gratitude was offered from the poor to the rich, from the powerless to the powerful, from children to their parents, from human beings to God.

Can love be forever?

In Plato’s Symposium, Plato defines love as the desire for the eternal possession of the good.

This last kind of gratitude, which is the basis of all others, is not always a rational affair. The Jewish (and Christian) God can be vindictive and hard to make sense of, as the story of Job illustrates. And the God of the Bible is still a person, if only a remote and invisible one.

It is really a totally new concept when we today speak of the gratefulness that we feel because of a good day, the fine weather, or the fact that we are alive. As opposed to even the Christians’ gratitude towards God, this abstract gratefulness is truly without object and, in a sense, all-encompassing. It is also interesting because, if one thinks it through, it actually negates the difference between happy and unhappy influences on our lives.

Because it seems that we should only be grateful for something good done to us, a “benefit” received. But already the Stoics had seen that sometimes, benefits come disguised as burdens. On the other hand, Greeks bearing gifts are not always to be trusted, even if one would like to get one’s hands on the gift.

It was the 14th Dalai Lama who, in one of his books on happiness (I forget which one), first alerted me to the thought that our virtues would actually not be worth much if there were no “bad” people on whom we could exercise them. For what is the value of one’s patience if there is nobody out there towards whom we can be patient? What is the value of forgiveness if there is no one to forgive?

A Stoic is an adherent of Stoicism, an ancient Greek and Roman philosophy of life. Stoics thought that, in order to be happy, we must learn to distinguish between what we can control and what we cannot.

In a more general way, it is clear that every single one of our virtues would be meaningless if the world did not present us with an opportunity to exercise it. I can only be patient, good, forgiving or brave because I have to confront people who are annoying, who tempt me to be bad, who wrong me, or whom I have good reasons to fear. In this sense then, every bad thing in the world can be seen as something that, instead of being truly bad, is actually a disguised blessing: an opportunity given to me to show and exercise my virtues: my goodness, my honesty, my courage; and without those things all the cultivation of my character would be utterly meaningless.

This is what makes that third version of gratefulness truly unique. Not only is it a gratefulness without object; it is also based on a non-dualist view of life, in which the good and the bad are both necessary; and in which they both work together to elevate and perfect the human character.

In our own lives…

The Dalai Lama’s idea is so simple and yet so immediately meaningful and obviously right: that we should treat every obstacle in our way as a chance to improve ourselves, and that we should see everyone who challenges our patience, who invites us to hate them, who lies to us, who threatens and damages us as a benefactor. We need to shift our view and recognise that what these people are really doing is to give us an opportunity to be better than we would otherwise be.

As part of our year-long challenge to live these philosophies in our everyday lives, let us try to realise, in the coming week, that all-encompassing gratefulness in our own lives. The first few times it will probably be hard and not work at all, but with some practice it will become easier and easier to not spontaneously react with impatience, revulsion or aggression to those whom we (perhaps with good reason) dislike. Instead, we can practice to see them as opportunities, like the Dalai Lama says, to exhibit our virtues; as necessary objects to our virtues, without whom we wouldn’t be able to do anything good in our lives at all.

◊ ◊ ◊

Thank you for reading! I’d love to hear what you think! Please do tell me if you found this idea as interesting and fruitful as I did, or if it left you indifferent. You can leave a comment below!

Notes

[1] Emmons, The Psychology of Gratitude. An Introduction. In: Emmons R. A. and McCullough M.E. (eds). The Psychology of Gratitude. Oxford University Press, 2004.

Cover image: Thomas Aquinas, theologian and philosopher (1225-1274).