How to lose friends and influence people

Logical fallacies and their use

Who does not know that feeling when a discussion becomes unfair, as if sabotaged? You make a good point, but suddenly the person you’re talking to says something odd, absurd or irrelevant. Say you advocate for salaries to keep up with inflation when someone replies that in the good old times, real men worked harder instead of complaining. You ignore or try to gloss over this weird statement, but soon the discussion changes, your concerns are undermined. You feel like something slipped through your fingers, while the other side smirks with pride.

Some such conversation tactics even have names: red herring, whataboutism, slippery slope, non sequitur, etc., and anyone can mistakenly employ them from time to time. But they are most often used deliberately because of just how effective they are when trying to confuse the other side, to undermine, redirect and downplay their worries. Yes, a person doing this will quickly become unbearable and likely lose friends; however, such strategies help one quickly rise to the top of the political ladder.

Should we simply learn how to live with logical fallacies 1 or are there ways to heal our societies from the most virulent ones? Before we can attempt to answer that, let us look at some historical examples:

I

Nowadays, it is common knowledge that women are humans too, but in many parts of the world, they were historically treated as if they belonged to other species. That is why, in a 1792 book, Mary Wollstonecraft argued for the rights of women to receive proper education, to be part of the political life and generally for moral equality between the sexes. Though the book was mostly well received, there were some especially sleazy counterarguments. In a satirical response, philosopher Thomas Taylor retorted that if women were to have equal rights to men, then so should cats, dogs, magpies and other animals. Not only this, but he ‘hoped’ others would venture to write ‘treaties on the rights of vegetables and minerals.’ To prove beyond any doubt Wollstonecraft’s hypocrisy, he also mentioned how she, ‘though a virgin, is the mother of this theory, often, as I am told, eats beef for mutton.’

Now, of course, we can very well see what happened there: the topic of the discussion was changed to something absurd. This is a clear example of narrative control; the joker who makes such a statement wins no matter what. Either you recognise that women and animals are not equal, to which they’ll claim you are a hypocrite or you mention how animals deserve moral consideration too, which they’ll laugh off as dumb and impracticable. So that, even though the basic principle of equality means equal consideration of interests and ‘equal consideration for different beings may lead to different treatment and different rights’ (Peter Singer), try even making such an argument after the discussion was changed from ‘let’s treat women nicer’ to ‘so you think horses should vote?’

II

There is an 1803 book with the very grim title of Practical Rules for the Management and Medical Treatment of Negro Slaves, in the Sugar Colonies, where the author makes the following argument:

‘It appears, therefore, that slavery is prohibited by philosophy, not by theology; and I am doubtful whether the principle, upon which that prohibition is founded, may not, when urged to the extremity to which it may fairly be carried, lead also to the condemnation of many other of the practices of men, which are now deemed perfectly consistent with moral rectitude; for who that denies their dominion over their own species, will be so hardy as to dispute their empire over the rest of the animal world?’

You see what the author did there!? He undermined the anti-slavery movement as merely a trivial ‘philosophical’ pursuit and not anchored in serious ‘theological’ morals, even though many abolitionists were also deeply religious people. He then changed the subject to animal rights, which was seen as quite the ridiculous idea in those times.

I encountered this dreadful argument in one of Brandon Fisichella’s videos 2, where he mentions other ideas the slave-owners were cultivating: that the abolitionists did not care about the fate of the poor white workers or how this whole idea of justice for the slaves was just a clever advertising strategy used by companies that did not use slaves. Now, we live in the future, and it is obvious to us how disingenuous such arguments were, but, as Brandon reminds us, those were actually quite effective at the time and similar arguments are used to this very day against those who advocate for better workers' rights, to use just one obvious example.

III

One logical fallacy saw so much use during the Cold War that it got the name of whataboutism. It goes a bit like this: someone from the US will decry the lack of human rights in the Soviet Union, to which the response will be, ‘But what about the racism in the US?’ Or, perhaps, a Soviet ambassador asks, ‘By what right is the US invading other countries?’ to which the American counterpart will respond, ‘But what about the people of Eastern Europe under Soviet occupation?’ Needless to say, this way of arguing was useful only at shutting down genuine constructive conversation. Anything, even Reagan’s jokes, was probably better at breaking the wall between the two sides than such empty shows of moral superiority.

◊ ◊ ◊

Be it whataboutism, red herring or a plethora of similar strategies, Fisichella reminds us they function to undermine, downplay and redirect the conversation. And they are damn useful! So useful in fact, that we are constantly encountering them nowadays too. Let me give just two examples, which happen to be causes that I am passionate about, although the issue is much more far reaching.

Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022 in a colonial war of conquest, which forced millions of people to become refugees. My home country of Romania and my adoptive one, Poland, both received refugees, especially the latter. But just around the time refugees arrived, so did a sneaky argument along the lines of, ‘Look at those expensive cars the Ukrainians are driving! Why should our tax money go to them when there are poor people in our country who need help?’ Undermine, downplay, redirect!

Now, what a heartless way of thinking. There is no surprise that a minority of Ukrainians afford pricey cars – so do a minority of people in all other countries. It is also a fact that we live in big countries where we can simply do two things at once: help refugees for a while and also care about local wealth inequality. Not to mention the EU covered a lot of the costs for helping refugees anyway. But such arguments are of little consequence: the small yet vocal group of locals who only saw the cars and not the humans just needed an excuse not to care. Perhaps some of those who couldn’t stop talking about cars are genuinely confused. Be this as it may, what a coincidence that the same people are usually those who never do anything to help poor people in their own countries anyway.

The other cause I am passionate about is animal ethics. During my youth, I worked as a shepherd, so I know quite well how animal products are made. I also openly share that my veganism is morally motivated. Many people do not care about the matter or just say, ‘Good for you,’ but there are those who’ll feel the need to shout, ‘Hypocrite!’ So, they tell me, ‘You know, you can only be vegan because poor people are exploited all over the world. Why do you care more about animals than humans?’ or ‘Don’t you know plants have feelings too? So, vegans are basically worse than people who eat meat.’ Remember Thomas Taylor from the first example in this article? He’d surely shed a tear seeing how his wish came true and his legacy is safe: there are now lots of people defending the rights of vegetables, but oddly enough, they only do it when talking to a vegan!

Ideally, in an honest conversation, you can argue how caring about animals will likely make the world better for humans too, especially for the workers on farms and people who suffer first-hand from pollution, etc. But the discussion has been redirected: instead of animal ethics, it has rather become a question of mathematics: ‘How much human misery, animal exploitation and climate disasters are acceptable for some to enjoy steaks?’ The rarest, however, is to have constructive conversations with ‘vegetable rights activists.’ Interestingly, you can turn to a vegetarian philosopher for a serious discussion 3 about what it would entail to truly morally consider plant sentience. As of now, ‘vegetable rights activists’ do no more than Taylor did when it came to feminism 200 years ago: undermine, downplay, redirect!

What to do?

To make it clear, sometimes changing the conversation is just the polite thing to do. It is also perfectly fine to simply say, ‘I do not want to talk about this’ if a discussion comes to a point where, well, you just don’t want to continue it. These are not the situations we were exploring here, though. Rather, we looked at narrative control aimed at undermining an argument, at downplaying its importance and redirecting the conversation. If conscious of their actions, the person doing it knows what they are up to and they are willing to use dirty tactics to achieve their goals. Fisichella argues there is no real good way to respond to such tactics, but being able to identify them helps. Generally, the more people aware of said tactics, the less effective they should be – for someone using them is usually not open to honest conversation, but at least you can smell their game and even have a good laugh at their scheming. I believe there are a few more things we can do.

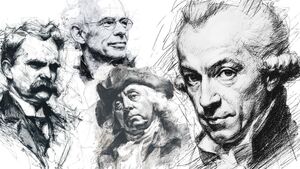

The study of philosophy can help with the task by exploring the most commonly used logical fallacies, by learning how fallacious arguments are made and what politicians are prone to exploit (for an example, Philosophy Tube has a video 4 on this logic). Heck, even reading Schopenhauer’s The Art of Being Right will be quite a good start. I certainly don’t know any simple way of moving our societies towards fairer, more honest futures, but when we live in times of gross unfairness, perhaps there is a morality in using the tools we derided in this article against the status quo (sometimes the master’s tools will dismantle a house built on lies). Certainly, the enemies of freedom and fairness are not shy to use them. How many minds were enchained while laughing?

Honesty and wit can help too. Now, these usually do not win against bullets, but they can prevent them from being shot. When talking to regular people, it is good to try and find the common ground and explore how you can work together towards common interests. If they are propagandised, simply being an honest, nice person will do a lot to remind them about the humanity in others. When talking to a**holes or grifters, though, outwitting them is often the more important tool, although you’ll have to be ready to face all the dirty tricks in the book, some of which we have seen in this article. But our societies can get better through conversations. You can’t shame the shameless, but you may just be able to undermine their authority!

Finally, there is hope when having genuine conversations with people close to you. I remember to this day that time a friend shared with me some women-specific struggles and every so often I’d interrupt her with remarks like, ‘Yes, women face sexual assault, but so do men’ or ‘Yes, women have to apply make-up, but men have to shave, and do you know how dangerous it is to have a sharp blade next to your neck?’ It didn’t take long until she had enough of this and told me directly, ‘Petrică, you know what your problem is? You do not listen to what I say. Yes, men face serious issues too. But why is it that every time a woman speaks, there is a man like you interrupting or changing the subject?’

I blushed. I was instantly humbled and for good reason. Shortly after, I apologised and learnt my lesson. Years later, we are still good friends and she forgot about this little dialogue. But I did not. Now I try to listen to what people have to say. It is not always easy, but it is worth it. Sometimes I learn new things, like the conspiracies or fallacies I’ve told you about in here. And even if by the end of a discussion, my arguments could not reach the other person, at least they were listened to and not just immediately judged or their worries summarily dismissed. It is the start of better conversations.

Sources mentioned

Fallacies | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Link.

Fisichella, Brandon. “Slavery’s Most Dangerous Argument.” YouTube, 8 Jan. 2025. On YouTube.

Tomasik, Brian. Bacteria, Plants, and Graded Sentience. Link.

Singer, Peter. All Animals are Equal, in Animal Rights and Human Obligations, ed. Regan, Tom; Singer, Peter. pp 148 – 162, 1976, PRENTICE-HALL, INC., Englewood Cliffs, N.J.

Wollstonecraft, Mary. A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: With Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects. 1891. Free online at Internet Archive.

Philosophy Tube. “Logic” YouTube, 31 July 2020. On YouTube.

Many thanks to Stanca for all the great conversations; without them, it is likely this article would have never been written. I am grateful to Kristyna and Mariia too, for reading early versions of the texts.

◊ ◊ ◊

Petrică Nițoaia is a former shepherd, passionate about philosophy and animal ethics. He writes mainly on the ethics of food production, wild animal suffering, human rights and philosophical pessimism. He finds philosophy and history not only fascinating but also fun and useful for making the world a more joyful and fair place for all.

Petrică Nițoaia on Daily Philosophy: