Thales of Miletus

A stroll through the history of philosophy

If you like reading about philosophy, here's a free, weekly newsletter with articles just like this one: Send it to me!

Welcome to a new series of posts, where we will leisurely stroll down the history of philosophy (mostly Western philosophy), having one quick look at each of the major thinkers of the past three thousand years or so. Come along, enjoy the views, and meet the greatest minds of human history!

First, at the side of the path we’re following, sits old Thales of Miletus. Miletus was a great city, home of many a famous man, long before Athens became the centre of the Greek world. Almost all of the early Greek philosophers came from here. Not only Thales (~624–548), but also Anaximander, Anaximenes, Leucippos (who started the ancient theory of atoms), Hippodamos, who is the father of urban planning, and the first to say that streets should be built straight and cross each other at right angles; and, finally Aspasia, the mistress of Perikles and first lady of Athens at its most glorious moment in history. They all came from this little town on what is now the coast of Turkey. There’s a Greek research site that has created a 3D model of ancient Miletus and has some beautiful maps and pictures of what it may have looked like. Here is one:

Screenshot of Ancient Miletus model. Head over to fhw.gr for more images and maps.

Thales of Miletus himself seems to have been more of a general-purpose scientist, rather than a typical philosopher. Wikipedia calls him a mathematician because much of what we know of him has to do in some way with geometry. He calculated the distance of ships and the height of pyramids by measuring triangles.

On March 28, 585 BC, Thales of Miletus was supposed to have observed an eclipse of the Sun. A short history of the difficulty of knowing the date.

One day, somebody asked Thales (or so a story goes), if he was so clever, why wasn’t he rich? Thales, of course, being a philosopher, wasn’t interested in money; but the question annoyed him, and in order to show his critics that a philosopher could get rich if he wanted, he used his skills in predicting the weather to determine that the coming olive harvest would be more bountiful than ever. Without telling anyone, he rented all the olive presses around Miletus for the time of the harvest, and when people wanted to press their olives into oil, he made a healthy profit, proving to his doubters that a philosopher could, indeed, get rich if he wanted.

His philosophy itself has always puzzled more traditional thinkers, beginning with Aristotle, who didn’t understand it either (and said so).

For one, Thales said that everything comes from water, or that water is at the beginning of everything.

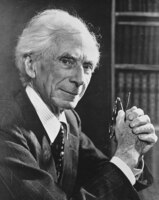

This is strange, for in our experience quite a number of things are bone dry and seem to exist even without water. Bertrand Russell, in his History of Western Philosophy, tried to take Thales' side on this matter by pointing out that hydrogen atoms comprise a big part of the universe, and what is water if not, mainly, hydrogen? If you’re shaking your head now, well, yes. Poor Thales surely hadn’t thought of the abundance of hydrogen in the universe.

Thales of Miletus: everything is made of water. Photo by YUCAR FotoGrafik on Unsplash

What then? In what sense is everything made of water?

We have to notice here that all the examples that Thales of Miletus gives (as reported by others, because we don’t actually have anything written by Thales himself), are examples of life: seeds, plants, living nature. And, obviously, here it does make sense to speak of water as the essence of life on Earth.

Further, Thales seemed to think that the soil of the Earth itself originates in water. This becomes more understandable if we realise that by the 15th century, the river supplying Miletus with water had deposited so much silt that the once coastal city had to be abandoned. Today, Miletus lies 10km away from the seashore. So, in a sense, it was the water that brought with it the soil. Or, with just a little bit of a perspective shift: it is the water that contains the soil, carries it along, and then evaporates or flows away, creating the Earth. Whoever doubts that water is the origin of soil needs only to look at the 10km of barren land that now lies between the busy harbour of ancient Miletus and today’s Aegean Sea.

Photo by Ivan Bandura on Unsplash

Thales of Miletus also held the belief that everything was filled with souls. This sounds crazier than it was meant to, and the key here is to remember that for the ancient Greeks, the “soul” often meant just a force of moving. Aristotle speaks of the “vegetative” souls of plants, the “sensitive” souls of animals and the “rational” souls of men. Thales even said that a magnet had a soul because it could attract filings of iron that would move towards it. So “soul” really means nothing more than “the origin of autonomous motion,” and in this sense, many things indeed have “souls.” That’s all for Thales. If you’re interested in more, Wikipedia has quite a good overview. The main fragments about Thales of Miletus can be found in an English translation here.

Thanks for reading, and I hope you had fun! Stay with me, next time we’ll stroll along to the other Presocratic philosophers! Subscribe so you don’t miss any posts!