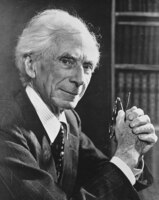

Gilbert Ryle (1900-1976)

Are philosophers like map-makers?

If you like reading about philosophy, here's a free, weekly newsletter with articles just like this one: Send it to me!

Portrait by Rex Whistler. Source: Wikipedia

Gilbert Ryle was born in 1900, the son of a doctor with interests in philosophy and astronomy. He studied in Oxford and became a lecturer in philosophy in 1925. He published his main work, The Concept of Mind, in 1949.

Ryle had many interests and is somewhat difficult to put into a neatly labelled drawer. One thing he did was oppose Cartesian dualism.

Cartesian dualism

What does this mean?

It has to do with how many fundamentally different kinds of things one assumes to be in the world. There are chairs, cars and apples, of course. But, in the end, these are all of the same kind: material things. They have a length, a height and a weight. One can drop them and break them.

But not all things are material. We have thoughts, for instance. Thoughts don’t seem to have a length or a weight. People don’t get any heavier if they are thoughtful, nor is not-thinking an effective way to lose weight. Rene Descartes (who is the man behind ‘Cartesian’ philosophy and also the starting point of all modern thought, 1596-1650) accordingly thought that there are two fundamentally different substances in the world: on the one hand, material things, like chairs and apples. And on the other, thoughts. Mental processes, he said, must be different from matter, because obviously thoughts don’t have a length, or a weight.

The human mind is unique and we know of no other comparable phenomenon in the universe. The philosophy of mind (monism, dualism, computationalism) attempts to explain what exactly the mind is.

This general idea is called ‘dualism’ in the philosophy of mind, because it divides the world into two (Latin: duo) fundamental kinds of things. It is also familiar to us from Christian religion, which assumes that a human being is composed of both a material part, a body, and an immaterial part, a soul. The soul is what ‘thinks,’ and it is thought to survive the death of the body and go to heaven or hell.

This kind of thought was common long before Descartes, and even before Christianity. Plato already distinguishes between a (higher, purer) world of ideas, and a (lower, dirtier, less perfect) world of things. For Plato, things are just the imperfect ‘copies’ of the ideas. This is also a dualist approach.

Plato and Christianity

Plato’s ideas about the eternal world of perfect Forms provided a template upon which Christian philosophers could build their vision of the eternal, transcendent realm of God.

Behaviourism

Ryle is one of the many philosophers who disagreed. He thought that seeing thoughts as ‘immaterial things’ is wrong. Instead, one can always translate a statement about thoughts into a description of a behaviour that is equivalent to these mental processes. A belief (for instance, that one is rich), will lead to a series of behaviours expressing richness: buying a car, renting a big house, and so on. A mental state like “fear” will lead to behaviours like running away from the feared thing, screaming, calling for help, and so on. Love, in contrast, leads to entirely different behaviours. In fact, one cannot well distinguish the mental state itself from the associated behaviour: What is the meaning of saying that one feels love for another person, if this love does not lead to particular (‘love-appropriate’) behaviours towards the other person? Is there at all something that is the mental state of love (or fear, or any other mental state) and that is not expressed in suitable behaviour? The doctrine that mental states are nothing but the behaviours that express them, is called behaviourism.

In the end, Ryle disputed that there are particular ‘things’ that philosophers are dealing with. Medicine deals with illnesses, atomic physics with atoms, and oceanography with oceans. It is tempting to think of philosophy of being just another science like that, a science that deals with thoughts, concepts, arguments: ‘things’ of the mind. Ryle disagreed. He thought that philosophy is a particular way of examining just the same things that make up our everyday reality.

Introductions to Philosophy

We discuss the three best introductory books to philosophy.

Philosophy as map-making

In a famous analogy, he described philosophy as cartography, the science of making maps. The villager who has a knowledge of his village and the cartographer who draws up a map of the village don’t have different subjects: they both examine the village. But the villager has a personal, historical approach to it: This house is John’s house, this is the blacksmith’s, this is the doctor’s. The cartographer, in contrast, describes the village in more abstract terms: as streets, directions, elevations: in the same terms as he would describe every other village. In this way, he seeks a more general description of the same village. The object of his study is not a different object; it is just described in a different way.

◊ ◊ ◊

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this, why not subscribe?