Monism, Dualism and the Philosophy of Mind

Do we have a soul?

If you like reading about philosophy, here's a free, weekly newsletter with articles just like this one: Send it to me!

What are minds made of?

The Philosophy of Mind is the area of philosophy that asks what human minds are made of and how they work. We all agree that we have a mind. We can think, we can feel, we can take decisions, we can relate to others, we can do physics and play chess. But what, exactly, is that elusive mind?

Animal minds

The human mind is unique and we know of no other comparable phenomenon in the universe. The question of what exactly the mind is and how it works has troubled philosophers for as long as philosophy exists. One problem arises when we think of things that have “less mind” than we do. A dog, for example, a cat, a pig. Or: a pigeon, a sparrow. A palm tree. A Christmas tree.

Some of these clearly do have mental processes very similar to ours, but they are much more limited. Still, we do say that they have a mind. But where does this end, and why? Does a bird have a mind? Birds can navigate, they can hunt for food, they can build complex nests out of materials they collect and arrange themselves. Do they not deserve to be thought of as intelligent in some way, of having a kind of mind? And what about insects? Individual ants or bees don’t seem to do much mental processing, but in a group they use rudimentary forms of language to communicate, and they have surprisingly strong opinions about what they want and how to achieve it. Ants will help each other, even sacrifice themselves to let others reach a food source or to defend their nests. Bees will describe the location of food in terms of distance and angles to the sun, much like a seaman would do in the days before GPS. And what about mold? Yes, mold. Some slime molds, e.g. Physarum polycephalum, can find the best way between two points on a substrate, find its way out of a maze, and make intelligent menu choices (the latter being something that even most humans fail at).

Does the mold, then, have a mind?

So the one question is where the mind ends and mindless life begins. Is there even such a point? Is there any life that is entirely devoid of mind?

Your ad-blocker ate the form? Just click here to subscribe!

Do we have souls?

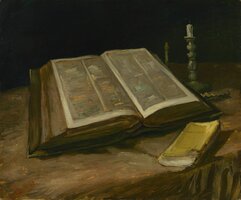

In a Christian framework, we would probably identify the mind with the immortal soul of man. The soul is specific to humans and this justifies, for a Christian, the sharp distinction between humans and everything that is not human and, therefore, automatically inferior to us. Genesis 1:26:

Then God said, “Let us make mankind in our image, in our likeness, so that they may rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky, over the livestock and all the wild animals, and over all the creatures that move along the ground.”

That soul is supposed to be immortal and to survive the death of the body. How exactly this works out is unclear and the way we imagine the afterlife has changed over time. But some version of life after death is common to many religions: Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, all share some belief in the continued existence of a soul after the death of the human body.

It is surprisingly difficult to make sense of this question. It leads, for example, to the further question what it means for something to “exist”. Chairs, pens and fridges exist in a very crude, material way. That’s the obvious meaning of existing. But non-material things also seem to exist quite nicely. Plato’s philosophy exists, and it is not identical with any particular book in which it is printed. Plato’s philosophy is an abstract kind of thing, a collection of ideas. It can exist in different media: as Youtube videos, as a podcast, a university lecture or a book. On the other hand, the dream I had last night surely also exists (after all, I saw it), but it is a strictly private thing, experienced only by me. My pain from touching a hot pot in the kitchen undoubtedly exists, but does it exist in the same way as my dream, a fridge, or Plato’s philosophy? And how do numbers exist? Does 2 exist? Does the result of 237123 times 73298115 exist before anyone has calculated it? Does the biggest whole number exist? Or an even more intriguing question: Does the queen of the United States exist? The US never had a queen, but we can perfectly well think of that concept. We know what a queen is. We can imagine one ruling over the US. Does the concept then exist although the manifestation of the concept in the real world does not?

From these examples we can see that it’s not clear at all what we’re saying when we say that the human soul exists or doesn’t exist. Surely the concept of a soul exists and we can talk about it in the same way as we can discuss a hypothetical queen of the US, or a (non-existent) country between Spain and Brazil that is home to the rare pink chimpanzee and where the soil is entirely composed of ice cream. I can imagine such a place, so it must exist at least as an image in my mind. God “exists”, clearly, because religions have been the reason for endless wars in human history. Countless people have lost their lives in the service of their religion, so how can we claim that the reason that they were killed does not even exist? Something did exist, at least for them, at least as a reason, a justification for their actions and their sacrifice.

You might say that perhaps then we should distinguish between the idea of a thing and the material realisation of that thing. But this does not solve all the problems. For example, a religious person, or a Platonist, would insist that God and the Platonic Forms of things exist in a more concrete way than just as ideas in the human mind, although they might not exist as material objects. And what about human consciousness? Does this exist and in what way?

Philosophy of mind: Monism, dualism and dreaming the world

So it seems that we can distinguish at least three different ways in which we can talk about the human mind.

First, we could say that mind and body are the same thing. The mind is nothing but the functioning of our neurons, our nerve cells in the brain, and when we’re dead, we’re dead. There is no immortal soul, only this body. This would be a kind of materialist monism. Monism, as opposed to dualism, comes from the Greek “monos,” meaning single, sole, or alone. For a monist, there’s only one kind of thing in the universe, and everything is made of that one substance. In the case of the materialist monist, this would be physical matter (there are more distinctions to be made here, but let’s put them aside for the moment). If a soul is supposed to be immaterial, it couldn’t exist, according to this view.

But a monist doesn’t need to be a materialist. In an interesting reversal of this position, we could try to argue that, yes, only one substance exists, but this is not matter; it is the soul. We would then be saying that only spiritual substances exist and everything material is an illusion. This position has never been widespread, but we do find echoes of it in Plato, in Buddhism and in the idea that the world is just dreamed up by spirits or shamans (some forms of shamanism). Or even, in its most modern form, the idea that the universe we live in is just a very advanced computer simulation and that we are nothing but computer programs that some alien intelligence has created (the Simulation Argument).

On the other side of this debate, dualists would argue that there are (at least) two different kinds of things in the universe: material things and soul-like-things. These two are made of entirely different materials, and/or have entirely different properties. This is essentially what Christians believe in when they talk of the distinction between the mortal body and the immortal soul of man. The problem with this approach is that there doesn’t seem to be any way of proving or disproving the claim in a scientific way. All our science operates only on a physical level and it’s very hard to imagine what kind of experiment could possibly prove the existence of an entirely immaterial soul. Perhaps if we had really strong evidence for telepathy or the survival of consciousness after death, we would be in a stronger position to argue for a dualism like that. But so far there is little convincing evidence that such phenomena really exist. This is not to say that dualism is wrong — only that it is, at the moment, impossible to prove whether it is correct or not using the science that we have. And this is why the belief in a life after death remains exactly that: a belief that we can share or reject, but not a statement that we can scientifically prove.

This short primer explores René Descartes’ Meditations on First Philosophy, his contribution to rationalism, and his impact on early modern philosophy.

Computationalism: Are we just computers?

Finally, one central question in the philosophy of mind is whether we are just computers.

Obviously, this would be based on some kind of monist understanding of the mind. But it goes further than that. The thesis that the mind is a computer would commit us to saying that everything that our minds do are just examples of computations. Language would be a kind of computation (which is plausible). Love would be a kind of computation. Abstract thought would be computation. The sense of self and of our own consciousness would also be, in the end, nothing but a computation.

This “computational theory of mind” might then also work backwards. If all the mind does is computation, then computers, which can perform computations, should be able to also do all that the mind does. A view like that would open up the possibility of having, in some near future, real computer minds and computer persons, and would perhaps force us to accept “computer rights” in the same way that we claim “human rights.”

We will go into more detail on some of these fascinating ideas in future posts, so stay tuned!

◊ ◊ ◊

Andreas Matthias on Daily Philosophy: