August 22: Happy Birthday, Geneva Conventions and Ray Bradbury!

If the Geneva Conventions didn’t exist, Ray Bradbury might have invented them.

If you like reading about philosophy, here's a free, weekly newsletter with articles just like this one: Send it to me!

What possibly could an international treaty and the magician of Science Fiction have in common, besides a birthday on August 22?

The First Geneva Convention

Today in 1864, representatives of twelve states and governments signed the first of a series of Geneva Conventions, the Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies in the Field. The original treaty had only 10 very short articles. It dealt only with the humane treatment of wounded soldiers in the field and the status of neutral medical personnel, particularly of the Red Cross, who attended to them.

Since then, the ten articles have slowly expanded to 64, and the twelve countries who signed the Geneva Convention(s) have grown to 196.

They are a curious set of rules: a self-imposed obligation to harm one’s enemy as much as is necessary and useful to one’s ends, but not more than that. And an obligation to treat someone you want to kill and annihilate with the civility and respect that you would grant your friends. In that, the Geneva Conventions carry echoes of both Christian sentiment (love your enemies) and medieval ideals of chivalry, which included never to strike a defenceless opponent in battle. They are, in this sense, uniquely rooted in Western history and traditions, and it would be an interesting project to see whether other cultures (Islamic? Chinese-Confucian? Buddhist?) provide similar cultural archetypes. Perhaps we will go after this question in a future post.

What Is a Stoic Person?

A Stoic is an adherent of Stoicism, an ancient Greek and Roman philosophy of life. Stoics thought that, in order to be happy, we must learn to distinguish between what we can control and what we cannot.

But even earlier than the Middle Ages, we find similar thoughts. Stoic philosophy teaches that all human beings are of equal value, and that one can never be justified in placing one’s own interests over another’s. This, much later, became the central idea of Kant’s ethics: the principle that we are all infinitely valuable as persons, and that therefore no human being can ever be used by another “as means only.” Instead, we must all treat each other as ends, as human beings who have an infinite worth, just by virtue of being human.

Photo by Elijah O'Donell on Unsplash

That’s the high-minded part of the Geneva Conventions. But that’s not all there is to them. Because, think about it: if we were so noble and if we were able to recognise all these truths about being equal and infinitely valuable, why would be waging wars at all? Why don’t the Geneva Conventions just outlaw war? Despite all their talk about protecting the wounded, they never say a single bad word about the very real and obvious reason why there are wounded people on the battlefields. Why not just call for an end to wars?

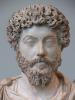

Because, behind all the high-minded philosophy, there’s the animal nature of man, and it’s inseparable from man’s goodness. One of the most prominent Stoic philosophers, the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius, wrote his Meditations down in his tent, while on military campaigns in what is today Germany and Austria. He wrote about the value of humanity while ordering his armies to decimate the barbarians, to kill their children and to burn down their villages. Christianity’s central symbol throughout the ages has been the cross that was used to kill the very man who said that we should be nice to each other. Medieval knights formed their romantic notions of chivalry while marching towards Jerusalem, where they would mercilessly deal out death and destruction to innocent local populations. And the Geneva Conventions were inspired primarily by the horrors that Henri Dunant, founder of the Red Cross, saw in the battle of Solferino.

April 26, 121 AD marks the birthday of Roman Emperor and Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius, who still inspires us today with his sense of humility and duty.

Our highest standards for human behaviour are rooted in human cruelty, war, destruction and misery; and, in fact, they would have little substance if it were not for the pools of blood out of which they have grown.

Human greatness is not in that we are nice to each other by nature. If we were unable or unwilling to harm each other, there would be little value in being good.

In Quentin Tarantino’s “Pulp Fiction,” there is the scene where the killer Jules talks about his conversion. Here’s what he says:

And that’s it. That’s the point of the Geneva Conventions. We are trying hard. We are the tyranny of evil men, and we know it. But still, we’re trying real hard to be the shepherds.

I’ve always felt that if one day the thing happened that the Christians expect, and God came down from the Heavens for the Second Coming and the end of the world, and there was the Day of Judgement: what would we say? It would be hard to defend humanity. We’ve made such a mess of the world. We’ve never, in thousands of years, stopped killing each other, killing innocents, slaughtering children, using the most horrible means we could think of. We have done nothing about poverty, and very little about slavery and sexual exploitation. We have failed in bringing freedom and democracy to our societies. We failed to keep peace among us. We have irreparably destroyed the natural environment, uprooted the forests of the world, poisoned its waters, driven our fellow creatures to extinction. We’re not nice. We truly are the evil men.

God would be looking down at us in His just anger, and demanding to see if there’s anything at all to redeem us, any little thing that would even remotely show that we are human.

Is there? There is.

We would say, yes, we are the evil men, we know. But see, here are the Geneva Conventions. Here is a memory of that day, an August afternoon in 1864, where we monsters all gathered in that place between the mountains, and for one tiny but glorious moment we showed the world that we have not given up on ourselves. They are a testament to the fact that, recognising what we are, we nonetheless will keep trying, real hard, to be the shepherds.

Ray Bradbury

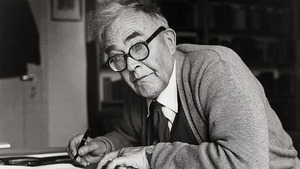

Bradbury in 1975. Photo by Alan Light, via Wikipedia.

And here’s where Bradbury fits in. If there’s one thing that makes his writing truly unique, it’s not the technical mastery of his plots, or his lavish descriptions, or his breathtaking use of vocabulary. Bradbury writes simply, often in the language of children, and his protagonists are often children themselves.

August 19: Happy Birthday, Gene Roddenberry!

Gene Roddenberry, creator of Star Trek (August 19, 1921 - October 24, 1991).

What singles him out from all the other writers of literature is his simple humanity. It is his ability to see very clearly how we are corrupt and lacking grace, but at the same time his unshakeable belief that we are also of the same stuff angels are made of. In the deepest abyss of Captain Beatty’s soul, Bradbury shows us the same longing for meaning and the same love of books that Montag himself feels. The space-priests who create an altar to fire balloons, the poor father who tricks his children into a pretend spaceflight, the Chinese Emperor who is forced to kill the inventor of the flying machine he has been dreaming of all his life… What unites these characters, despite their superficial differences is the belief, deep down, that they are all connected, all brothers, all travelling along the same path, on the same journey, all searching for the same moment of grace that will give their lives meaning and make them whole: just like children are, looking at the incomprehensible world all around them, bewitched by its mystery and promise.

If the Geneva Conventions didn’t exist, someone like Ray Bradbury might have invented them.

Happy Birthday, Geneva Conventions! Happy Birthday, Ray Bradbury!

Thanks for reading! If you liked this, please subscribe for more!