Kant’s Ethics: What is a Categorical Imperative?

A Daily Philosophy primer

If you like reading about philosophy, here's a free, weekly newsletter with articles just like this one: Send it to me!

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) is one of the greatest philosophers of modern times. His philosophical interests went in many directions. He asked questions like: Are space and time real and independent of human cognition, or are they just creations of our minds? He examined the concept of beauty and tried to make sense of what we find beautiful. But more important than these, at least in a practical sense, was Kant’s ethical theory: the question of how we ought to behave.

There’s a lot that one could write about Kant’s ethical theory, but if we want to summarise it in five minutes, it boils down to one principle:

Now, what are these principles?

Kant’s first form of the Categorical Imperative

First, Kant says, we must recognise that all human beings are equally valuable. We are all different from stones, plants and animals because we have what Kant calls “autonomy”: the ability to decide for ourselves how we want to act, what choices we want to make, and how we want to live our lives. Animals must follow their instincts, but we humans are free agents, able to even decide to sacrifice ourselves for a cause, for example. This shows that we are, indeed, special. More importantly, we are all of us special in this way. There are no humans who don’t have this ability to be autonomous. Everyone, regardless of skin colour, education, religious beliefs and length of nose, has the same ability to be an autonomous, free moral agent.

Photo by Petr Sevcovic on Unsplash

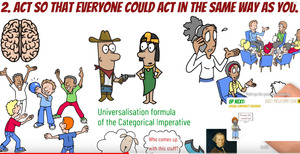

This also means that we have to respect everyone’s autonomy equally. If I do something, then everyone else must also be allowed to do that. I cannot claim to be “special” in any morally relevant way, since we are all equally autonomous beings that must be respected equally. And this, finally, leads us to what is called the First Form of the Categorical Imperative in Kant’s ethical theory (but don’t be scared of the words – the idea is pretty simple):

(Not exactly Kant’s words, but close enough).

When I claim to have the right to cross a red traffic light, for instance, I should ask myself: could I really want that everyone else also crosses red traffic lights? If yes, then it might be okay to do so. If not, then I shouldn’t do it.

The point here is not so much what I want, but what I can rationally want. This is a fine distinction. Even if I don’t care whether others cross red traffic lights, if everyone did it, then traffic lights would have no function, and then cars would collide at intersections and kill pedestrians, and eventually, the whole road traffic system would descend into chaos and become unusable. So it’s more than just my personal taste that’s at stake here: nobody can rationally want a world without traffic lights.

Kant’s second form of the Categorical Imperative

There’s a second test that Kant’s ethical theory proposes, and it’s this:

What does this mean? Perhaps the talk of means and ends is confusing. You have to imagine the end as being the goal of your action, whatever you want to achieve by performing that action. And the means are the instruments, the tools you use, and the way you take to get there. So when I am hungry, the lunch is my end. It’s what I want at this moment. In order to get it, I might take a bus, use a credit card, and order the lunch from a waiter. All these are the means I use in order to achieve my end.

A core feature of Kant’s ethics is his insistence on the value of one’s motivation for the morality of an action. As opposed to utilitarianism, Kant does not look at the consequences when judging actions, but only at what he calls the “good will.”

Now Kant thinks that it’s perfectly fine to use buses and credit cards as means. But what about that waiter? I shouldn’t use them only as a mean to my own end. So how do I avoid that? By respecting the waiter’s free decision (autonomy!) to serve me my lunch, in exchange for an appropriate amount of money as a payment. By paying for my lunch, I give the waiter the ability to use that money later in order to pursue their own goals: to raise their children, to go watch a movie, or to buy themselves a lunch in another restaurant.

But payment alone is not everything. I might be paying for my cheap T-shirt made through child slavery in some poor country, but I’m not treating these children as ends. Most of the money goes to intermediate businesses and almost nothing to these children who actually make my clothes. So Kant’s idea here is actually pretty demanding: that we need to make sure that all our actions are acknowledging the value of others as human beings, by treating them as ends and not only as means. This can be applied to families, where the members of a family will sometimes see the others only as means to their own comfort; or it may apply to an employment situation, where an employer might treat the employees as means to maximising their profit, as is often the case with store chains. It may also apply to the people who don’t want the local government to build a highway through their village. I, as a potential user of that highway, have a personal responsibility to respect the ends of the people who will have to live alongside it.

What is Utilitarianism?

Utilitarianism is a moral theory that states that the morally right action maximizes happiness or benefit and minimizes pain or harm for all stakeholders. Proponents of classic utilitarianism are Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) and John Stuart Mill (1806-1873).

One thing that is very important to Kant is that each one of us has their own responsibility to follow the moral law, to do what is right rather than what is wrong. We cannot outsource our morality and blame society, the government, or some political party we don’t like for whatever goes wrong in the world. Each one of us has to obey the two categorical imperatives, every day, in a thousand small decisions.

And this is what Kant’s ethical theory ultimately is all about.

◊ ◊ ◊

Andreas Matthias on Daily Philosophy: