What Is a Stoic Person?

Learning to control one’s mind

If you like reading about philosophy, here's a free, weekly newsletter with articles just like this one: Send it to me!

What is a Stoic person? On a prominent website, you find this description:

That’s quite misleading, and a good demonstration of why one shouldn’t use dictionaries to answer philosophical questions.

What Does ‘Stoic’ Mean?

A ‘Stoic’ attitude to life aims to achieve lasting happiness by staying calm, rational and emotionally detached, while cultivating one’s virtues.

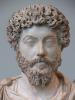

The Stoics were an ancient Greek and Roman school of philosophers, who counted among them a slave, a celebrated writer, and an Emperor of Rome (Epictetus, Seneca the Younger and Marcus Aurelius, respectively). Their world view was complex and included the study of the natural sciences, but one of the main principles of their theory of happiness was that:

One should clearly distinguish between events that one has control over, and those that one cannot control.

This is the basis of correct thinking and of reaching one’s maximum potential as a human being. Because only after we’re able to see what we can influence and what we cannot, we can approach these two classes of events in different, and appropriate, ways.

The events that I can control, I must control, the Stoic would say. It is my duty as a human being and as a citizen to use my power and my influence in society to the maximum extent possible, in order to benefit everyone who comes into the sphere of my control.

And this, in turn, has to do with the realisation that we are all equally valuable as human beings, and that our concerns, fears and loves all count the same, all are equally important. Selfish people, in the Stoic world view, are just mistaken about the importance of their own self. They are deluded, they fail to recognise that, to everyone else except themselves, they are “just another dude over there,” not better or worse than anyone else. The Stoic attempts to learn to see himself or herself in just the same way as he or she looks upon others.

Epictetus writes:

Since we are all equal in value and importance, we really don’t have any reason to be selfish. We should therefore exercise our control in such a way that we achieve the most benefit for all, not only ourselves. But this doesn’t mean at all that we should be indifferent, cold, emotionless or “blank.” Just the opposite. When a Stoic like the Emperor of Rome acts, he knows that his actions are going to affect all, and he would put all his wisdom, all his knowledge and all his passion into the attempt to act in the best, the wisest, the most beneficial way possible. Everything else would mean to neglect one’s duty to our fellow human beings.

April 26, 121 AD marks the birthday of Roman Emperor and Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius, who still inspires us today with his sense of humility and duty.

But the wise man also recognises that their power to influence the world is limited. Illness, wars, natural disasters, accidents, even attacks by other men cannot always be avoided. These things happen, but often we are powerless to change them.

If this happens, and only then, the Stoic would say that the right reaction is acceptance, what the Stoics called synkatathesis, assent. But the assent, the calm acceptance of the world’s evils may only be offered when the Stoic person is not able to act in a different way, when nothing they might possibly do would change the negative event.

When one is utterly powerless, then, and only then, acceptance becomes a wise option.

As long as the Stoic has any hope of winning, they will go on fighting, resisting, changing the world, trying to make it better, more just, more free and equal.

Marcus Aurelius, the philosopher-king, died far away from his home and his palace, in the cold mud of a battlefield in the forests of what now is Vienna. He didn’t need to. As the Emperor, he could have stayed in Rome, safe, enjoying the privileges of being the world’s most powerful man of that time. But he choose not to. Far from being emotioness and blank, he went out to fight and give his life for what he believed: to improve the lives of the people who had been entrusted to his care as a leader.

Leaning over a notebook under the flickering light of an oil lamp, every night after the day’s battle, he wrote a few sentences into his diary. _Notes to myself, he called it, and only later people decided to call it with the grander title “Meditations.” And this is what the Emperor wrote:

Begin the morning by saying to yourself, I shall meet with the busybody, the ungrateful, the arrogant, the deceitful, the envious, the unsocial. All these things happen to them by reason of their ignorance of what is good and evil. But I who have seen the nature of the good and I know that it is beautiful, and I who know that the bad is ugly, … I also know that it is just like myself. Not only of the same blood or seed, but that it participates in the same intelligence and the same portion of the divinity. I can not be injured by any of them, and no one can fix on me what is ugly. Nor can I be angry with my kinsman, nor hate him, for we are made for cooperation, like feet, like hands, like eyelids, like the rows of the upper and lower teeth. To act against one another then is contrary to nature; and it is acting against one another to be annoyed and to turn away. (Meditations, Book 2)

It is in our power to change ourselves. And every new day, every new morning, is a chance to become a little bit wiser, stronger, and greater than we have been the day before. This, not blandness and indifference, is the true attitude of the Stoic.

Your ad-blocker ate the form? Just click here to subscribe!

◊ ◊ ◊

Thanks for reading! Photo by Ken Cheung on Unsplash. Do you agree with Marcus Aurelius? Tell me in the comments!

The Stoic View of the Self

For the Stoics, everything that happens to us seems to have a special significance that the same event wouldn’t have if it happened to someone else.

Andreas Matthias on Daily Philosophy: