What is the Philosophy of Religion?

Does every religion need a god?

The philosophy of religion is a wide and varied field of study that is different from both theology and the history of religions. It touches metaphysics, epistemology, logic and many other areas of philosophy.

This is the start of a new series on the philosophy of religion, so make sure to not miss the upcoming articles!

If you like reading about philosophy, here's a free, weekly newsletter with articles just like this one: Send it to me!

Why religions matter

When we contemplate religions, a myriad of intriguing questions arise. Is there a fundamental difference between religious groups and other social communities? Must every religion involve a belief in a higher power, and must this necessarily be a personal God? Are religious practices and rituals necessary, or can a religion do without them?

Picture, for example, the fans in a football game stadium. They are united by a common interest, they form a closed social group, they have regular meetings at a special place of worship where they congregate and perform their weekly rituals and they even have an irrational belief in the powers of their football club. Are they a religion? If not, what is missing?

Is it a god? Does every religion need a god? But then, many religions don’t have anything like a god. Buddha, for example, was a human being, not a god. Daoism is a religion, but it does not have a god. The highest power in Hinduism is Brahman, but this name signifies an abstract principle, the ultimate reality of the universe, and not a personal god.

We might ask, why do these questions matter at all? After all, who cares. We could let anyone who wants to found a religion do so, and accept all sorts of communities as religions: Shakespeare actors playing in a park, a bus-load of tourists, a class of students. Wouldn’t that do?

The problem is that religions have a special status in most of our societies. For example, one might have to pay taxes differently, depending on one’s religion. In Germany, one has to pay a special “church tax” that goes to one’s church. Churches also are protected in terms of freedom of belief and expression. In Covid times, when public meetings were restricted, church congregations were often exempted. When social distancing was mandated by law, churches in some places could still perform the Holy Communion and have their believers share wine from the same cup. Sometimes, believers will be excluded from military service if they can prove that a particular type of service is against their religion. The right of particular groups to eat Halal or Koscher food has to be respected by the state. When the British tried to force Indian troops to handle a gun cartridge that had been greased with pig and cow fat, thus offending both Hindus and Muslims, the soldiers rebelled. This became one of the starting points of what is often called the Indian Mutiny in 1857.

The list goes on. All the special rights and obligations that believers derive from their religious affiliations can only be taken seriously if we can make sure that they are truly the expressions of religious faith, rather than, say, random opinions. We would probably agree that no Christian soldier should be forced to bomb an enemy church, for example. But should the same apply to a football-fan soldier ordered to bomb the enemy’s football stadium?

Photo by Jimmy Conover on Unsplash.

The questions in the philosophy of religion

We can organise the types of philosophical questions that are related to religion in a few different categories.

First, we have the so-called “conceptual questions.” These are questions about religious concepts, and what these concepts mean. For example:

- What is religion?

- What does the word “God” mean?

- What is “faith”?

These questions are mainly about definitions and about how to separate these concepts from other, similar phenomena.

Second, we have what we could call the “metaphysical questions.”

- Is there a life after our physical body perishes?

- Do we have immortal souls?

- What could life after death possibly be like?

- Do religious/mystic experiences really transcend the physical world?

- What is the relation between divine beings (such as God) and the physical world?

These questions are about supposed facts. I say “supposed,” because, although such questions seem to be asking about facts, it seems impossible to answer them using the methods and instruments of science. The question whether there is a life after death, for instance, is a meaningful question, as is the question whether there are immortal souls. But currently we not only don’t know the answers, we do not even have an idea of how, in principle, we could go about trying to find an answer. How could we possibly measure the presence of a soul? How could we possibly try to find out what happens to us after death? It seems that these questions entirely transcend what physics could possibly deal with, and this is why they are called meta-physical, which means “beyond physics.”

Third, we can identify what we could call “epistemological” questions. “Epistemological” means related to how we know things. For example:

- How can we know anything about the world beyond what our senses tell us?

- What is the difference between reason and faith?

- For example, how could I possibly try to prove that there is some kind of personal existence after death?

You see an important difference in this last one. When we talked above about metaphysical questions, we asked “is there a personal existence after death?” As an epistemological question, this turns into: “How could we possibly prove that there is (or isn’t) a personal existence after death?” The metaphysical question asks about a fact. The epistemological question asks about the possible ways of knowing, not about the fact itself.

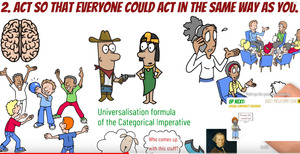

Finally, we have logic and argumentation questions. Logic questions would be:

- Are religious concepts logically consistent or do they cause contradictions?

- Can we find good arguments for the existence of God?

- How would we do that?

Here the focus is on the arguments themselves and their logic. Does religion have its own logic? Does religious language have different argumentative structures than everyday language? For example, believers may argue on the basis of what is written in a holy book, taking this book’s statements to be necessarily true. This is different from the way we argue in science, where the ultimate measure of truth is observation and experiment. But one could argue that science, too, needs belief: we must believe that our instruments work as we assume, that they measure what we think they do, and so on. When one looks critically at science, one finds that it often requires almost as much belief as religion.

Photo by Dan Cristian Pădureț on Unsplash

And many of science’s claims are impossible to verify: How do quantum theory and relativity relate to each other? What is inside a black hole? How did the universe begin? The answers to these questions are not only inaccessible to almost all humans except for a small number of specialists, they are also disputed among these specialists themselves, and the accepted truth about them changes every few decades. Physics theories don’t necessarily reflect any factual truth; rather, they are subject to fashions and often proven wrong after some time. Physicists have, at different times, believed that the vacuum of space is filled with ether, that things burn because they contain phlogiston, a flame substance, that the universe expands only, or that it expands and contracts, that there is one universe or many, that quantum uncertainty is just our inability to measure things precisely, that consciousness is a product of the brain, or that, recently in fashion, it is a fundamental property of reality. If one looks at all the wrong turns science has taken over the centuries, one has little reason to believe that it has a much stronger claim to truth than religion. We will come back to this idea later in this series.

Your ad-blocker ate the form? Just click here to subscribe!

Philosophy vs theology

When we talk about the study of religion, we have to distinguish the philosophy of religion from both the history of religions and from theology.

Although all three are studying religious phenomena, the history of religions tells us about what happened in the past in relation to some religion. For example, when was the Prophet Muhammad born, how did he live his life, how did Islam expand and gain new influence and territories over the centuries? These are some questions of the history of religions.

Theology, on the other hand, asks questions from within a religion. It assumes that we already believe in the specific religion and then it tries to justify or to question particular beliefs. For example, a Christian theologian may accept that Jesus was resurrected, and ask what this means for Christianity, while a philosopher may ask how plausible it is that someone can be resurrected from the dead.

B.V.E. Hyde: The Shortest History of Japanese Philosophy (1)

In this series of posts, BVE Hyde presents a short but complete history of Japanese thought. This first part focuses on Japanese Buddhism.

Religions and multiculturalism

Our modern societies are usually multicultural and include believers in different faiths. According to the Office for National Statistics,

over a quarter (25.3%, 2.2 million) of London’s population identified with a religion other than “Christian”, up from 22.6%, 1.8 million, in 2011. The next most common religious groups in London were “Muslim” (15.0%, up from 12.6% in 2011) and “Hindu” (5.1%, up from 5.0% in 2011).

And this is similar in many modern cities. As valuable as multiculturalism is, it also causes new problems that we did not have in earlier times in history. In ancient Greece, or in the European Middle Ages, societies were much more uniform, and one could assume that most people in an area would agree on their religious beliefs. There are geographical borders, even today, between the traditional lands of the Protestants and the Catholics in Central Europe. There is Hindu India and Muslim Pakistan. And there is, tragically once again, Jewish Israel and Muslim Palestine. These examples show three different ways how the relations of neighbouring religions can manifest themselves in political reality. From the peaceful coexistence of Lower Saxon Protestants and Bavarian Catholics to the deadly wars in the Middle East, conflicts between religions can often be unpredictable and, at worst, if they are fuelled by international political interests, impossible to resolve.

But even on a more theoretical level, the views of different religions can vary widely and make the coexistence of believers harder. For example, Jews rest on a Saturday. Christians, where they still rest at all, would do so on Sundays. This can have all sorts of practical implications, from employment contracts to the opening hours of shops. Buddhists or Hindus would believe in multiple lives and reincarnation. Christians, on the other hand, would assume that we have only one life, but that we need to preserve the integrity of our body even after death, so that it can be restored at the end of time. This can be very important in questions of organ donation, for instance, or whether we are allowed to cremate the bodies of believers. In a more far-fetched way, we might also see differences in how crime in a society is perceived. Religiously motivated terrorists might believe in and be motivated by some postmortal reward for their actions. Murder might be perceived differently if we believe in reincarnation than if we don’t. And so on. How can we make sure that we can still live peacefully together, even if we have different beliefs about these fundamental questions?

Should a Liberal State Ban the Burqa? by Brandon Robshaw, is a very clear, instructive and carefully argued book that shows off philosophy at its best.

And what can we do when we have to integrate such conflicting beliefs into one society? Can we somehow reconcile them? Or do we have to reject and suppress one of those beliefs, as many western European states did regarding the wearing of the Burqa?

The good news is that sometimes we may find that differences that seem crucial are actually only superficial. Many religions have very similar underlying beliefs and values, that are just expressed in different behaviours. This is one of the main theses of Aldous Huxley’s book The Perennial Philosophy, which we will discuss later in this series. If we look behind these obvious differences, we will often find that, for example, Judaism, Christianity and Islam, although they have so often been at war historically, have very much in common.

The philosophy of religion opens doors to understanding, appreciation, and reconciliation among all these different belief systems. It allows us to explore the questions at the heart of religious experience, and perhaps to harmonise contrasting beliefs in a world characterised by religious diversity. Whether we discuss conceptual, metaphysical, epistemological, or logical questions, the philosophy of religion is a dynamic and vital field that enables us to appreciate the rich tapestry of human spirituality.

Stay with us here in this newsletter and we will, in the coming weeks, talk more about different religions and the philosophical questions they pose.

Subscribe if you don’t want to miss the future parts in this series:

Andreas Matthias on Daily Philosophy: