Dao De Jing: A Hermit’s Manual

Daoism and the hermit life

The Dao De Jing, one of the main books of Daoism, has always appealed to hermits. In this article, we look at it through a hermit’s eyes and try to see why it has fascinated anchorites and recluses for more than two thousand years.

This article is part of a year-long series in which we examine six different philosophies of happiness and how they apply to today’s life. Find all the articles in this series here. Find all articles about hermits here.

The first part of this series on Daoism is here.

If you like reading about philosophy, here's a free, weekly newsletter with articles just like this one: Send it to me!

It is an impossible task to try and discuss the Dao De Jing in full within the length of one article, although the work itself is quite short. By the way, you may know it by a different transliteration, for example as Tao Te King; or by the name of its alleged author: Lao Tse, Lao Tzu, or Laozi. It’s always the same book, but over the centuries, different systems have been used to render Chinese characters in Western languages, and so we end up with all these variations in the English spelling, which really make no difference at all.

The main problem with the Dao De Jing, the “classic of the Way and the virtue” is that it is written in a highly ambiguous way: a sequence of 81 short paragraphs that resemble aphorisms and that can often be read and translated in wildly different ways. Even in the Chinese tradition, the book has sometimes been read as being close to Confucianism, and sometimes as being opposed to it. Sometimes as a religious text, and sometimes as a practical instruction book. It has inspired alchemists to search for eternal life (with the almost invariable result that they poisoned themselves, shortening rather than lengthening their natural life spans). It has inspired martial artists, Western writers and philosophers, and even Hollywood movies (much of the Force lore in Star Wars can be read as a variant of Daoist beliefs and practices). And it keeps inspiring, over thousands of years, hermits who leave society in order to live in the solitude of the remote mountains of China.

“The Daodejing often functions like a Rorschach test, in which readers find what they want to find,” writes Bryan van Norden, one of the best known Western teachers of Chinese philosophy, in his Introduction to Classical Chinese Philosophy (p.124).

Just a quick Google search reveals that intellectuals as diverse as fantasy author Ursula K. Le Guin, literary arch-satyr Henry Miller and soft-core sage Alan Watts have all written on the ideas of the Dao De Jing. Internet uber-professor Jordan Peterson (if you’re reading these posts for more than two weeks, you’ll probably be able to guess what I think of him), talks about it in an online lecture where he associates the Chinese Yang with masculinity, authoritarianism and fascism, and the Yin with the Unknown, with decadence and nihilism. Go figure, as the Americans say.

All this only underlines the futility, almost hubris, of presuming to add yet another interpretation of the Dao De Jong to the mix, especially given that I’m not an expert in Chinese philosophy, or Daoism, or any other related field. (Or any field at all, sadly).

The Dao De Jing, literally “The Classic of the Way and the Virtue,” is traditionally attributed to an author known only as Lao Zi, which means “Old Master.”

The Dao De Jing through hermit eyes

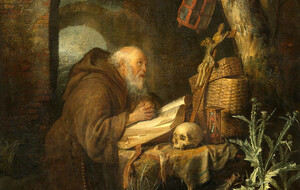

But this is also an unexpected advantage that we have, as readers of the ancient text who are interested in hermits: that our subject, the hermits who have used the Dao De Jing as their guide into solitude for more than two thousand years, often were also uneducated women and men. It is not, as a rule, the professors who go and live out their days in a reed hut somewhere on the edge of nowhere. Like Western monks and anchorites, the Asian hermits are often common people who have felt a calling to this lifestyle, who were touched by some of the words and ideas of Laozi’s book and who gave up everything in order to go on their lonely quest to find the wisdom that it promised them. (We will talk in a later article about a number of real Asian Daoist and Buddhist hermits and their stories).

So what we will do here is to have a look at the Dao De Jing from the perspective not of a philosopher, but of someone who feels at odds with the world, with the intricate complexities of so-called civilised society, and who feels the calling to leave this life and take to the mountains. Which passages of the Dao De Jing would speak to someone like that? What would they find in the classic book to support their project of searching for wisdom in the wilderness?

Let’s see.

Hermits, from the Greek “eremites,” (=men of the desert), are found in all cultures and at all times. In this article, we look at the phenomenon of hermit life as a whole, before we go into more detail in future posts in this series.

The dualist world of distinctions

We talked in the previous article already about the difficulties of translating the Dao De Jing. We’ll therefore stick here with one of the most classic translations, that of James Legge, which you can find in full here. But we may also contrast this translation with the one by A. Charles Muller (1991), to be found here.

Legge: The Dao that can be trodden is not the enduring and unchanging Dao.

The name that can be named is not the enduring and unchanging name.

(Conceived of as) having no name, it is the Originator of heaven and earth;

(conceived of as) having a name, it is the Mother of all things.

Muller: The Way that can be followed is not the eternal Way.

The name that can be named is not the eternal name.

The nameless is the origin of heaven and earth

While naming is the origin of the myriad things.

Now, if you are a hermit, ready to leave society, you are probably out to find something that society could not give you. The human world is truly full of things, stuff, clutter, consumer gadgets; but also arguments, distinctions, ranks, job descriptions, titles, politically correct and incorrect words. We have built a world full of things, material and immaterial, that have taken over so much of our attention that we are unable to concentrate any more and to find any satisfying, valid, eternal truth about the world and the human condition. The hermit presumably feels this cacophony of voices even more intensely than we non-hermits do. I can imagine that even this first verse must sound sweet to the ears of one who is unsatisfied with the impermanence of our everyday affairs, with the seemingly important tasks in one’s job that never lead anywhere, yet cause constant anxiety, with the myriad things that require our attention without every paying us back with meaning and wholeness.

And if “naming” is to blame, the world of dualist distinctions, then the “nameless”, in contrast, promises to quiet the mind, to still the cacophony of voices in our heads, to heal us from the assault of the world on our restless senses. This directly invites the prospective hermit to turn his or her back on society and to head to a place where there is no language, no names, no distinctions; and where one’s attention can be directed towards the wholeness of one’s being.

Living in a circular universe

Modern ecology underlines this conception of the world as a series of cycles that feed into each other. As in the famous Yin/Yang symbol, day and night are not opposites to be seen separately, but complementary parts of a fluid experience that swings from the one to the other. The same is true of youth and age in a human life, of beauty and ugliness, of knowledge and ignorance, of health and illness. One could argue that the ecological misery of the modern world is caused in part by our desire to separate these two aspects of all things into a part which is “useful” and another part which is “garbage”. Useful things turn, in time, into garbage, but we have lost the sense of the necessary cyclical recreation of usefulness from that “garbage”, creating those immense dumps of garbage that fill up our world.

In a Daoist world-view, plastics would be seen as the abomination that they are: a thing that has only one useful side and whose “used-up state” is impossible to recycle back into its useful state. Plastics disrupt the balance of heaven and make it impossible for our world to stay on the cyclical path of creation and destruction, by producing a thing whose destruction does not lead to a complementary act of creation. In contrast, the hermit’s hut and all its mechanics are, ideally, completely embedded into the cycles of nature. The hermit eats and drinks and their metabolic products return into the soil where they fertilise the next crop that the hermit will consume. The building materials for the hermit’s hut are natural materials that will eventually degrade and decompose, only to return back to the soil and grow new trees and leaves that will serve to renew the hut’s construction. And so on.

Non-action

Legge: Therefore the sage manages affairs without doing anything, and conveys his instructions without the use of speech. All things spring up, and there is not one which declines to show itself; they grow, and there is no claim made for their ownership; they go through their processes, and there is no expectation (of a reward for the results).

Muller: Therefore the sage abides in the condition of wu-wei (unattached action).

And carries out the wordless teaching.

Here, the myriad things are made, yet not separated.

Therefore the sage produces without possessing,

Acts without expectations

And accomplishes without abiding in her accomplishments.

This emphasises the point. In civilised society, one cannot “manage affairs without doing anything.” The myriad things need to be separated, so that we can have specialised jobs: the plumber, the bus driver, the professor, the advertising expert. For the hermits who live in their huts, the world is an undivided whole, and they take on all the different roles. The hermit is builder and water supplier, plumber and farmer, priest and settler, all in one: the myriad things are made, they are here, all around him: but they are not separated.

Aristotle’s theory of happiness rests on three concepts: (1) the virtues; (2) phronesis or practical wisdom; and (3) eudaimonia or flourishing.

The last will be the first

This is almost Biblical in its message that the last will be the first, and the first last (KJV, 20:16). It also seems to be an inspiration for the Daoists’ search for physical longevity, their quest for immortality, which led to a Chinese alchemical tradition not much different from the Western one.

And what is the way to put one’s own person last, in order for one to reap the promised rewards? In this society, putting oneself last is not easy and one’s life will be made more difficult than necessary. To escape the rat race, the best way is not to freely assume the role of the last rat in the race, but to step out of the race altogether. The hermit, therefore, will not take with them any material goods, any comforts from their previous life. Putting oneself last means to let go of every symbol of worldly status, it means to live in poverty and to trust in the ways of nature to keep one alive.

The excellence of water

There are a number of things to unpack here.

First, water, the lowest and most common of the things we ingest, is called “excellent” (in other translations: good, virtuous) by the sage. Its simplicity and abundance does not take away from its excellence or virtue.

This excellence is due to the water’s property of benefiting all things. This is interesting. It means that the goal of the hermit should not be to isolate themselves and stay away from society, but, as Bill Porter explained (see the last part of this series), the hermit’s isolation is the means to a further end: to educate and to teach, to “benefit all things” by spreading the wisdom and the insights that the hermit has acquired throughout the years of solitude. And, indeed, in movies and books on Chinese hermits (we will see examples later on), we see hermits sometimes having multiple disciples around them. The hermit’s life is not necessarily solitary forever. Once the wisdom has been acquired, once the Way or the nature of the Dao has been glimpsed, the hermit, like the water, becomes a source of benefit for the world.

And, finally, there is this talk of doing something “without striving.” This is, according to most Daoism experts (including van Norden, e.g. on p. 127 of Classical Chinese Philosophy), one of the core messages of Daoism: to achieve an effect in the world without really trying.

This has often been misunderstood. The point is not to “not act,” as if lying idle on a sofa would be the ultimately virtuous state of man’s existence. Rather, the ideal of human activity is to be “like water.” Water does a lot of useful work: from irrigating plants and keeping animals alive to even powering hydroelectric dams, no one could say that water is uselessly lying around. But all these beneficial effects are caused in the process of the water simply following its essential nature and the laws of gravity, without ever trying to flow uphill, to stop flowing, or to flow faster or slower than the laws of nature dictate.

A Stoic is an adherent of Stoicism, an ancient Greek and Roman philosophy of life. Stoics thought that, in order to be happy, we must learn to distinguish between what we can control and what we cannot.

It is interesting how similar this is to the Stoic ideal of acting in accordance with the laws of nature, of accepting what one cannot change; or with Aristotle’s description of the “sophron” man, who does what is right spontaneously, as the result of long practice. Think of handwriting, or walking: if you are a beginner in these skills (like a small child would be) handwriting and walking require a lot of attention to get right; from time to time you will write something wrong, or stumble and find yourself on the floor. Writing and walking, for the child, require immense effort to perform well.

On the other hand, we grownups are able to do both very easily, without even trying. When you jot down a note, you do so without thinking about the mechanics of writing. When you walk, you don’t even notice what your legs do and how you perform the miracle of balancing upright. This is “action without trying,” or “non-action,” as the Daoist would have it. We are doing something valuable when walking and writing; we are not idle. But we do what we do in the mode of a skilled performer, without needing to do it consciously, without needing to try. In this mode of performing, the activity is easy and fun, and it feels so natural that it doesn’t tire us, it doesn’t require our attention, it doesn’t require our will-power, grim resolve, or a Kantian sense of duty. For the skilled performer, life becomes play.

◊ ◊ ◊

Thanks for reading! Do you agree? Did I forget to mention something? Leave a comment below!

Bryan van Norden’s Introduction to Classical Chinese Philosophy covers in short chapters the main systems of Chinese thought, from Confucianism and Daoism to even a short overview of the 20th century. It’s an easy read that, nonetheless, gives a good impression of what Chinese philosophies are about. Kindle ebook here.

Amazon affiliate link. If you buy through this link, Daily Philosophy will get a small commission at no cost to you. Thanks!

Cover image by Huper by Joshua Earle on Unsplash.