Unpacking Descartes’ Meditations

A Daily Philosophy primer

If you like reading about philosophy, here's a free, weekly newsletter with articles just like this one: Send it to me!

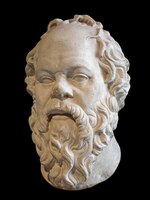

As one of the most influential philosophers of the early modern period, René Descartes' Meditations on First Philosophy has become a cornerstone of Western philosophical thought. In this beginner’s guide, we will explore the key concepts and arguments of Descartes' Meditations, including his method of doubt, the Evil Demon argument and the Wax Example.

We will also examine the significance of Descartes' contribution to rationalism and his impact on early modern philosophy. Finally, we will address some common criticisms of Descartes' work and talk about why his Meditations are still relevant today.

Descartes and the Meditations

René Descartes was a French philosopher, mathematician, and scientist who lived in the 17th century. He is widely regarded as the father of modern Western philosophy due to his contributions to the field of epistemology, which is the study of how we acquire knowledge about the world. Descartes' Meditations on First Philosophy, published in 1641, is a series of six philosophical meditations in which he attempts to establish a foundation for knowledge that is certain and that cannot be doubted.

The Meditations are called “on First Philosophy” because they aim to examine what comes “first,” before all other knowledge about the world. Before we can perform any science, any observations, or create any theories, we must first be certain about what we can know and what we cannot know, and how trustworthy our sources of knowledge about the world are. This is what “first philosophy” is about. Aristotle had used the same words to describe his own study of what “being” and “existence” mean, and the word is often used in philosophy to describe metaphysics, the study of the very basic questions that are beyond physical knowledge.

The Meditations are written in the first person and take the form of a personal journey of doubt and reflection. Descartes begins by questioning the reliability of his senses and the certainty of his beliefs.

He ultimately arrives at the conclusion that the only thing he can be certain of is his own existence. Because if one didn’t exist, how could one think and arrive at any conclusions? So the fact that we think, which we can be certain of, since we are still thinking even when we question the certainty of our existence, is the reason to be certain that we exist.

This conclusion, famously expressed in the phrase “I think, therefore I am,” serves as the basis for Descartes' subsequent arguments.

Understanding Descartes' method of doubt

One of the key concepts of Descartes' Meditations is his method of doubt.

Descartes employs this method as a way of systematically questioning and doubting all his beliefs in order to arrive at a foundation of knowledge that is certain. The method of doubt involves rejecting any belief that is not absolutely certain, regardless of how plausible or intuitive it may seem.

For example, although I see a table standing here in front of me, I cannot be entirely certain that there is, indeed, a table right here. I might be asleep and dreaming. I might be under the influence of drugs. Or the table might be some kind of elaborate hologram or painting that looks real but is actually not really there.

Through the method of doubt, Descartes raises questions about the reliability of our senses, the possibility of deception by an evil demon, and the limitations of human knowledge. By doubting all of his beliefs, Descartes is able to arrive at a foundation of knowledge that he believes cannot be doubted: the fact that we exist as thinking things.

Of course, saying that “something thinking exists” does not mean that we can be certain of our everyday, personal existence. I could still be mistaken about the properties of my body, about my name, about the way my house looks. The only thing that I can really be certain of is, strictly speaking, that “something that feels like me, thinks.”

The overall aim of Descartes’ philosophy is to found science on a secure and absolutely certain footing. Without that anything built by science would be open to doubt following from the weakness of its foundation.

Despite his use of the method of doubt, Descartes was not really questioning the existence of tables and other things in the world. His doubt was, as we say, a methodological doubt: a way of forcing himself to think about which knowledge was really certain and which was not. As opposed to a sceptic, who would question all knowledge, Descartes only used his doubt as a tool in order to arrive at what he thought was certain knowledge.

The Evil Demon Argument

One of the most famous arguments in Descartes' Meditations is the Evil Demon argument. This argument posits the possibility that an evil demon, with the power to deceive, could be manipulating our perceptions and experiences in such a way that we are unable to distinguish reality from illusion.

The Evil Demon argument is a powerful challenge to traditional notions of knowledge and certainty, as it suggests that even our most basic beliefs about the world may be subject to doubt and uncertainty. However, Descartes ultimately concludes that even if an evil demon is deceiving him, he still exists as a thinking thing, and this fact cannot be doubted. After all, I must exist in order to be deceived.

The Wax Example and its significance

Another famous example from Descartes' Meditations is the Wax Example. In this example, Descartes reflects on the nature of perception and the limitations of our senses. He considers a piece of wax, which can be perceived through the senses as having certain properties such as texture, shape, and color. However, when the wax is melted, all of these properties change, and yet we still recognize it as the same piece of wax.

The question is, therefore, what exactly makes this piece of wax itself? How can we recognise it as identical to itself, even though its properties have all changed?

The Wax Example is significant because it illustrates the limitations of our senses and the importance of reason in understanding the world. Descartes argues that while our senses may provide us with certain information about the world, it is only through reason and understanding that we can truly grasp the nature of things. It is only through reason that we can know that we are still holding the same piece of wax in our hands.

This is supposed to be a counter-argument to empiricists, who would claim that we can only gain reliable knowledge about the world from our senses. Descartes' Wax Example makes clear, at least in his opinion, that the senses are not reliable sources of knowledge at all.

Rationalism and its influence on Descartes' philosophy

Descartes' Meditations are often associated with the philosophical tradition of rationalism, which emphasizes the use of reason and logic in understanding the world. Descartes' emphasis on the importance of reason in his philosophical project reflects the influence of this tradition.

Rationalism is significant because it represents a departure from traditional forms of knowledge that rely on authority, tradition, or experience. In Descartes' time, knowledge was still often seen as backed up by the authority of either the ancient philosophers, like Aristotle, or church figures, like Thomas Aquinas. Much of philosophy was taught as an exercise in interpreting these old sources, rather than an attempt to generate new knowledge. This older tradition of philosophy, which Descartes was very much opposed to, is known as Scholastic philosophy.

Descartes was aware that trying to derive knowledge from the authority of others is not a reliable way of gaining actual knowledge. Aristotle was mistaken about many scientific facts, for example. So something new was needed: a way to generate new knowledge, new insights, that would be more trustworthy than mere tradition.

But what?

For natural scientists like Newton (who lived at around the same time) this source of knowledge was experiment and observation. But Descartes was sceptical of that. If dreams can deceive us, if hallucinations and drunkenness can make it impossible for us to judge the truth, what reason is there to trust our senses?

For Descartes, as for other rationalists, the most certain truths come from logic itself. The best example of that was always seen to be Euclid’s geometry. Since the time of ancient Greece, Euclid’s geometry had been used to describe the world in terms of lines, triangles, circles, areas and volumes – in a way that strictly derived every single fact logically from what had been established before. There couldn’t be any uncertainty about the sum of the angles in a triangle, for instance. And rationalist philosophers dreamed of a philosophy that would be just like that: as certain as those theorems about triangles.

The significance of “I think therefore I am”

The phrase “I think therefore I am” is often referred to as the “cogito,” from its Latin form “cogito ergo sum.” It is one of the most famous and influential statements in Western philosophy. This phrase encapsulates Descartes' claim that the only thing we can be certain of is our own existence as a thinking things.

The cogito is significant because it represents a radical departure from traditional forms of knowledge and authority. By focusing on the self as the foundation of knowledge, Descartes challenges traditional forms of authority, like the Scholastic philosophy he himself had been taught as a young student.

Descartes admired her intelligence and Leibniz stood at her deathbed, but during most of her life, she was a penniless refugee. Meet Elisabeth, Princess of Bohemia.

The Mind-Body problem and mind-body dualism

A second topic that Descartes discusses in his Meditations is the relationship between mind and body, or thoughts and the material world. This is known as the “mind-body problem,” and it is one of the most important topics in philosophy.

Descartes proposed that mind and body were two distinct substances that interact with each other, but are separate entities. This view has been debated ever since, and has had a major influence on philosophy, cognitive science, artificial intelligence, but also potentially on theology, up to this day.

Descartes' distinction between mental states (such as thoughts) and physical states (such as bodily movements) has had the effect of perceiving us humans as bodies that are controlled by a separate mind, much like Christian dogma would assume that there is a moment at birth where a soul enters the body of the fetus – and another point at death, where the soul exits the body and goes on existing without it.

Source: Midjourney.

This conception, called “mind-body dualism” has been questioned by much of modern science, which is, essentially monist: it assumes that the only things that exist in the world are physical substances. In relation to the mind, modern neurophysiology would assume that the mind’s functions are produced by the (physical) brain, rather than that there is a separate “mind-substance” that causes the body to think.

But, in the end, nobody knows at present how the mind really works.

The human mind is unique and we know of no other comparable phenomenon in the universe. The philosophy of mind (monism, dualism, computationalism) attempts to explain what exactly the mind is.

Descartes' impact on early modern philosophy

Descartes' Meditations had a profound impact on early modern philosophy, influencing thinkers such as John Locke, Baruch Spinoza, and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. Descartes' emphasis on the importance of reason and logic in understanding the world, as well as his focus on rationality as the foundation of knowledge, had a lasting influence on the development of modern Western philosophy.

After Descartes, the split between rationalist and empiricist schools of thought widened. Spinoza and Leibniz roughly fall into the rationalist camp, which maintained that the only certain knowledge comes from what we can know prior to experience.

On the other hand, empiricists like John Locke and David Hume rejected this approach and thought that we can only know anything by obtaining information about the world through our senses.

This split came to a temporary truce with the philosophy of Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), who argued that we need both our senses and the built-in thought patterns of our minds in order to make sense of the world in the way we do.

Your ad-blocker ate the form? Just click here to subscribe!

Criticisms of Descartes' Meditations

Despite its lasting influence, Descartes' Meditations have also been subject to criticism. Some philosophers have criticized Descartes' emphasis on the self as the foundation of knowledge, arguing that it leads to a solipsistic and individualistic view of the world. Others have criticized Descartes' reliance on reason and logic, arguing that it neglects the importance of experience and emotion in understanding the world.

Another criticism is that one cannot easily build up a comprehensive theory of knowledge on just the insight that “I am.” As much as this is certain, it seems almost impossible to conclude anything else, anything more substantial from this one certain bit of knowledge. Well, I exist. But what now? What else can I know for certain? – Turns out, not much.

Descartes himself had this problem and he had to rely on assumptions about God to get him out of this difficulty. “I know that there must be a God,” he thought, “and this God, because He is always good, cannot be a deceiver. Therefore, I can rely on God to show me the truth about the world and to give me certain knowledge.” – This is roughly how Descartes' argument continues, and then he derives all sorts of knowledge from the assumption of a non-deceiving God who controls and guarantees the truth of our perceptions.

It is quite obvious, though, that this belief in a trustworthy God does not go well with Descartes' commitment to radical doubt. If I really doubt everything, why would I not doubt the existence or the goodness of God?

Conclusion: Why Descartes' Meditations are still relevant today

In conclusion, Descartes' Meditations on First Philosophy continue to be relevant today because they challenge traditional forms of knowledge and authority and open up new possibilities for understanding the world. While his emphasis on reason and logic has been subject to criticism, Descartes' focus on the self as the foundation of knowledge remains a powerful and influential idea in Western philosophy. His work also set the stage for the rest of early modern thought that discussed the same questions that Descartes had. Other philosophers, inspired by Descartes, either followed him or rejected his conclusions – but both were influenced by him and continued on the path that Descartes had plotted out.

Whether we agree with Descartes' arguments or not, his Meditations serve as a reminder of the importance of questioning our beliefs and assumptions and engaging in critical reflection and inquiry. In an age of increasing polarization and dogmatism, Descartes' emphasis on reason and independent thought remains as relevant today as it was in the 17th century.

If you’re interested in learning more about philosophy and the great thinkers who have shaped our understanding of the world, be sure to check out our other articles and resources on the subject. Whether you’re a beginner or an experienced philosopher, there is always something new to discover and learn.

Rene Descartes: Meditations. One of the classics of early modern philosophy, but surprisingly readable even today. A must-read for every student of philosophy.

Amazon affiliate link. If you buy through this link, Daily Philosophy will get a small commission at no cost to you. Thanks!

Andreas Matthias on Daily Philosophy: